Fred Rutman shares his journey of surviving 20 clinical deaths, his resilience, and the life-changing benefits of intermittent fasting. This is a story of hope and transformation.

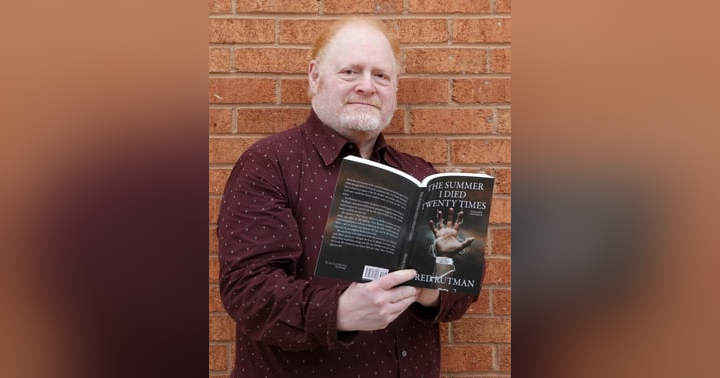

In this riveting episode of Life-Changing Challengers, host Brad Minus interviews Fred Rutman, author of The Summer I Died 20 Times and host of the Dead Man Walking podcast. Fred shares his extraordinary journey of surviving over 20 clinical deaths due to a rare heart condition that caused his heart to stop unexpectedly. Through vivid storytelling, Fred recounts his experiences with medical trauma, misdiagnosis, and the challenges of living with multiple pacemakers. Despite the odds, Fred has emerged stronger, advocating for resilience, hope, and self-advocacy in the face of life’s greatest challenges.

Fred also discusses the transformative power of intermittent fasting, his upcoming sequel Dead Again, and his passion for helping others find meaning through adversity. His humor, insight, and unwavering optimism make this an episode you won’t want to miss.

Episode Highlights:

- [1:00] – Fred reflects on his upbringing in Winnipeg and the early challenges of growing up with undiagnosed medical conditions.

- [15:30] – The moment Fred was first clinically dead and the misdiagnoses that delayed his treatment.

- [27:50] – His life with pacemakers, including malfunctions and surgeries, and what it feels like to be “repeatedly dead.”

- [39:00] – Fred’s out-of-body experience during one of his deaths and the lessons it taught him about life and resilience.

- [50:15] – The transformative effects of intermittent fasting on his health, including reversing diabetes and chronic pain.

- [1:02:30] – Fred’s advice on building resilience, maintaining hope, and advocating for yourself in the medical system.

Key Takeaways:

- Resilience is a muscle you can build through challenges, community support, and self-advocacy.

- Hope is a powerful, free resource that can help you navigate even the darkest times.

- Intermittent fasting can be a life-changing tool for improving overall health and reversing chronic conditions.

- Building a strong community is essential for emotional and physical survival during tough times.

Links & Resources:

- Fred Rutman’s Website: RepeatedlyDeadFred.com

- Fred’s Books:

- The Summer I Died 20 Times – Available on Amazon.

- Upcoming sequel: Dead Again – Stay tuned for its release.

- Dead Man Walking Podcast: Available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.

- Follow Fred on Social Media:

- Instagram: @repeatedlydf

- LinkedIn: Fred Rutman

If you enjoyed this episode, please rate, review, and share the podcast. Your support helps us bring more inspiring stories like Fred’s to listeners worldwide.

Have an idea or feedback? Click here to share.

Contact Brad @ Life Changing Challengers

Instagram: @bradaminus

Facebook: @bradaminus

X(Twitter): @bradaminus

YouTube: @lifechangingchallengers

LifeChangingChallengers.com

Want to be a guest on Life-Changing Challengers? Send Brad Minus a message on PodMatch, here.

Brad Minus: [00:00:00] And welcome back to another episode of life changing challengers. Again, I'm your host Brad minus as always. And I am so excited for this podcast. This one's going to be epic. Ladies and gentlemen, I have Fred Ruttman with me. He's an author and he's a podcaster, of the Take Dead man walking podcast.

And let me tell you something, this is going to be so interesting. And there's a reason why he calls it that. And what you're going to hear is going to astound you. It might even piss you off a little bit, but it's all for a good reason. Yeah, let's get started.

So Fred, how you doing today?

Fred Rutman: I'm doing great, Brad. Thanks for having me on.

Brad Minus: Let me ask you a question. What was your childhood like? What was the compliment of your family? Where did you grow up? And what was it like to be Fred as a kid?

Fred Rutman: Well, I grew up in a place called Winnipeg, which is, actually the geographic. center of the entirety of North America. So if you [00:01:00] flattened out the map, Winnipeg, right in the middle of it, it's simultaneously the coldest and flattest place on earth. And, it's the prairies. It's just. I didn't know what a hill was until I moved to Toronto.

So I get that

Brad Minus: I'm in Florida, so it's flat. It's just absolute flatness there.

Fred Rutman: I guess I had a typical upbringing, you know, family of five, mom and dad both worked. I played a lot of hockey. I played rugby in college, a lot of sports, but I also had a lot of challenges and I didn't know I had the challenges, which is, quite common for people with invisible disabilities, which is what I have.

I have great relationship with my sister, great relationship with my brother. My parents have unfortunately passed. I spent a lot of time playing hockey in the very, very cold outside.

Brad Minus: You grew up in Canada. Yeah, that's what I thought people did there. You either sat in front of the fire, you [00:02:00] played hockey, or tapped maple syrup, you know, that's what Americans believe.

No, I'm kidding. , so basically you said, a nuclear family. Yeah, brother and sister. Where did you line up between your brother and sister I'm the youngest. Oh, you're the youngest. You're the baby. Okay, cool what'd your parents do for a living?

Fred Rutman: My dad worked for the Company called London Life, which I guess would be the Canadian equivalent of Metropolitan Life. And my mom did the payroll for the school board. So, you know, if teachers weren't exactly nice to me, I could say, you know, your check could get lost. Of course it couldn't.

Brad Minus: Yeah.

So that was good. And did you have a regular family dinner? Was there a day that was always the same? Like I always talked that Friday nights for my parent was always movie and pizza we always go to a movie and pizza.

Did you have something like that? You know, was it dinner always around the table?

Fred Rutman: Yes. Friday night dinner was always around the table. We were encouraged to bring [00:03:00] friends.

Brad Minus: Nice.

Fred Rutman: I had cousins that were living in Winnipeg while they were going to university and they would often come over.

Sometimes my grandmothers would come over. So, my mom came from that generation where they weren't really bare mental with food choices. So it was, you know, usually just seasons with Lipton's onion soup or something like that.

Brad Minus: I still season my stuff with Lipton onion soup. Cause I come from the same generation. And I love it. , so. When did you start playing hockey? In like, early early, or was it middle school? Was it high school?

Fred Rutman: I was probably six when I first lacd on the skates. And, yeah, I'm not very tall. I'm 5'7 I'm about as wide, so when I was in the right mood, I could be a very aggressive player, and you couldn't knock me down because I had such a low center of gravity.

I could be a little bit of a [00:04:00] terror, or sometimes I could be a little bit of a Wayne Gretzky.

Brad Minus: All right, got some skills either you were skillful or you were the enforcer sounds like

Fred Rutman: Is it five days a week that I was playing?

Brad Minus: Did you and you played in college too?

Fred Rutman: So even though, when I played in the beer leagues later on, there were still guys that are like 40 years old thinking they're going to get, you know, to play on Wayne Gretzky's wing or something like that. So they play way too aggressively. And it's like, chill, dude, you know, we've got jobs tomorrow.

We've got families to go home to.

Brad Minus: So where'd you go to university?

Fred Rutman: I went to the university of Winnipeg and the university of Manitoba. I went to the Asper school of business. And that's where I got my MBA.

Brad Minus: I have my MBA as well, of course, from Leipzig University.

Fred Rutman: We're from the same family.

Brad Minus: So you did, what was your [00:05:00] undergrad in?

Fred Rutman: My undergrad, was in geography. Which is hilarious because I'm colorblind. I cannot read a map.

Brad Minus: The terrain maps much, just absolutely kill you.

Fred Rutman: The weather maps weren't much easier.

Brad Minus: Oh, wow. No wonder you went and got your graduate degree. So what was your first job out of college?

Fred Rutman: Probably working for London life. I worked for the same company. My dad worked for different offices. And it was an interesting because so many of my dad's friends and cousins also worked at London Life.

These were people that had known me since, you know, a couple of days after I was born. And now they're my peers. So it was very interesting. You could literally go around my neighborhood in every 10th house. Was somebody who worked at London life

Brad Minus: oh, wow. That's obviously a [00:06:00] huge company. My first job when I finished college was with a company called country companies. That was the same thing. Country companies had was their, their, their headquarters was in, was in the same town as my, as my college. So it was like, I got to go the summer after I graduated and get indoctrinated.

For lack of a better term, and then we shipped over to Arizona to start working for them, which London life obviously is an insurance company. So as country companies, they're also an insurance company.

Fred Rutman: Is is the perfect word for it.

Brad Minus: Yeah. When did those start to, come to the surface?

Fred Rutman: Well, they were manifesting pretty much my entire life. It's just, I didn't know. You don't know what somebody else tastes or sees or how somebody hears something or how somebody feels something. So it turns out [00:07:00] in my mid thirties, I was told I had had a stroke at birth. And that just explained a whole ton of my life.

You know, the social awkwardness. my ability to verbalize things, to the point where nobody realized I was having all these problems. Doctors diagnosed me, I'll call them the brain trainers, because that's what they eventually did. They told me I had a severe right hemisphere dysfunction. So the stroke wiped out a good chunk of the right side of my brain.

So I can't visualize. This is a conversation I had with my roommate the other night. I can't visualize anything. I could, the example I gave her was like, you could see an ice cream cone in your hand as if it was actually there in your mind's eye. I can't, I cannot visualize [00:08:00] anything.

Brad Minus: Got a, and isn't that like something that you'd be go, we start early, right? Like our parents always say that stuff like that. Right. All right. You're two plus two. Think about two apples, two oranges. How many times, how many things you've got? Think about that. Visualize it. And I got that my whole life.

And here you just couldn't do that.

Fred Rutman: And I didn't know that I couldn't do it. Like I just thought I'm bad at this. So it turns out that I have a condition because of this called hemiparesis. So the left side of my entire body, Is slightly paralyzed.

Brad Minus: That could be tough.

Fred Rutman: Happens with stroke victims all the time, right?

Brad Minus: That, could completely hinder a hockey player. You would think

Fred Rutman: It did. It really did. I was really good at turning from my right to my left, not so good from left to right. [00:09:00]

Brad Minus: That's just, I mean, it's unfathomable really to, to someone that, you know, grew up healthy. Yeah, it's just absolutely.

Yeah, that is crazy. But they always say that, I mean, everybody says that white guys can't go to their left anyway. So

Fred Rutman: it's just a part of a pattern that seems to have evolved in my life of, not getting things diagnosed properly when they should have been diagnosed. Thankfully, I found out from these guys that I did have some challenges and we worked to overcome, still not completely recovered.

My parents felt horrible when we learned this, like they felt like they had failed as parents. Oh, geez. You guys, how would you have known? You're dealing with your own stuff. You're trying to make a living, raise a family. You're not medical [00:10:00] professionals. The teachers didn't pick it up.

Nobody picked it up. My family doctors didn't pick it up. The pediatrician didn't pick it up. How can you blame yourselves?

Brad Minus: Yeah, but I can see their point. You find out 30 years later that, at birth, you had a stroke, a parent is automatically going to Like feel that, I'm curious though, what brought you into the doctor in your thirties to actually end up with that diagnosis?

Fred Rutman: Well, I was struggling with certain aspects of my life. I was a seemingly high performer who wasn't performing again because of my verbal skills. And my sister had a friend who was doing a PhD, and her husband, this PhD student's husband, ran a clinic for people that had various brain disabilities.

So, you know, it took a long time for me to summon up the courage, get rid of my ego [00:11:00] and say, maybe there is something wrong with me. Obviously, there's something. And, did the tests, and got the results, and then What do you do? And they said, well, we've got this program. We can try you.

And I ended up, working with these guys for probably two and a half, three years. And because of them, I was able to go back to university and then I was able to do my MBA. It wasn't seamless, but it certainly put me in a much better place than where I was.

Brad Minus: Oh, well, I mean, that's amazing that they could take this, like you said, you couldn't visualize and had problems and you had the slight paralysis on the left side.

And now, you know, they were able to work with you enough to where you were able to be high functioning again and finish up your degree and go to graduate school. That's amazing.

Fred Rutman: Yeah, I'll still never make the NHL.

Brad Minus: I think you should be the first person that went through [00:12:00] everything that you did to make the NHL.

Fred Rutman: It.

Brad Minus: So, fred has written a book. The book is going to basically tell you where we're going with this. The summer I died 20 times, that's the name of the book.

I'm going to leave it like that and let you all sweat. What was your health like until this summer?

Fred Rutman: Oh, it's been up and down. You know, I've had a serious weight problem for most of my life. Probably around the time I got sick in 2009, I was about 340 pounds. That was pretty big. And I've worked hard to get down to about 220, do a variety of things, mostly intermittent fasting.

Brad Minus: Which is a

Fred Rutman: whole other story that's fascinating.

Brad Minus: Yep.

Fred Rutman: So, the summer I died 20 times is what actually happened to me. I was clinically [00:13:00] dead 20 times. And if the audience needs a definition of clinically dead, your heart stops beating for 30 seconds, And you also don't breathe for 30 seconds or more.

And that's what happened.

Brad Minus: Wow. So what was the medical conditions? What was the prevailing issue to get this started?

Fred Rutman: Well, your heart has nerve bundles in it. That tell it when to beat. So it's a whole electrical distribution system and mine started to die. They don't know why they have no idea why when the electrical stops working your heart stops beating kind of die.

So I would collapse and generally hit my head on whatever was the hardest object in the immediate vicinity. Until My body's backup [00:14:00] systems kicked in. My redundancies didn't kick in for the most part until we were probably like at the last redundancy that could start me up again.

So I had, the fact that I was dead, then I'd have all the head trauma from concussions and lack of oxygen. And doctors misdiagnosing me all over the place. We're not diagnosing you.

Brad Minus: What was the initial incident that, kicked this chain reaction off?

Fred Rutman: I was marking economics papers. I was a professor at the time. All of a sudden I died and, I was just, you know, on the desk and didn't know I died, you know, my heart just stopped. The dying part is easy. I think I wrote this in the book, you know, it's pretty easy to die.

Your heart just [00:15:00] stops and there you go. Coming back to life when all these redundancies in your body start to kick in, it's like the biggest electrical shock you can get. That's just all the systems trying to come back to life at the same time. And it's actually painful. Coming back to life is very painful.

It's, it's worthwhile. Being alive is certainly better than being dead. But, yeah, it, it was pretty rough.

Brad Minus: And then all of a sudden, if I'm saying this right, you just died, and then the redundancies kicked in and you said that that's painful.

What do you absolutely remember? You personally, not what people told you, but what you remember.

Fred Rutman: I remember coming back to alertness and I'm just pouring sweat, just like breathing really heavily because I'm in the serious coffin and pouring sweat, not really understanding.

At all, what had [00:16:00] happened to me? I didn't know. I thought maybe I had some sort of glue or food poisoning. It never occurred to me I was dead. Certainly, you know, it was exhausting. And I know some people say economics could be the death of them. To me, it literally was. And, I'm sure you've taken a few economics courses in your, in your day.

Brad Minus: Yes, I have my MBA as well. So yeah, absolutely.

Fred Rutman: Yeah, it's dry. And then, it just continually happened. And finally, I ended up going to emergency and the doctors kept trying to prove I was having a heart attack. Like they looked at me, middle aged white guy, really overweight, must be having a heart attack, except I wasn't.

But they were so zoned in, they were medically profiling me.

Brad Minus: Right. But you called it cognitive bias.

Fred Rutman: [00:17:00] That's just what they thought. That's the first thing that comes to mind and they couldn't move off their spot to say, you know, we've tested them 10 times for heart attacks and they've shown up negative.

Maybe we should try something else. I don't want to diss the medical system. I mean, every system has its. I just have to run into a ridiculous amount of the lower tier, of the medical system in a row. Like it's just

Brad Minus: the narcissism of them trying to force a diagnosis on you. That just burns me up. I mean, I can see them testing you three times, maybe three times.

10. That's literally, in my opinion, that's forcing the trying to force the diagnosis instead of moving on and trying to find something else.

Fred Rutman: Well, it wasn't until my 17th incident that, they actually figured out what was going on and they had put, a halter monitor on [00:18:00] me. So those are those, small medical device, probably the size of an iPhone.

And it records the intimacies of your heart's electrical system. And they had actually dismissed me from the hospital. It was a Friday afternoon. And I was supposed to go home with this. Recording and then come back, bring it back on a Tuesday or something. And I went to the washroom and my roommate, he might've been mafia.

I don't know. He's quite a character, but I had to use the washroom in the hall and I had a whole bunch more incidents and, cracked my head pretty good, broke my glasses, bleeding from my eye. And I went to the nurse station and she says, what the hell happened to you? She says, well, you know, we need your room. My roommate's like, there's no way in hell he's going out of the [00:19:00] hospital, I ended up staying and they were not very happy with me. But then when they read the halter monitor, they realized my heart was stopping and I wasn't having a heart attack.

I had this condition called, a full AV block, atrial ventricular heart block. My electrical died and then they scheduled me to have a pacemaker inserted probably four days later. And I had, I think, three more incidents while I was in the hospital. And I remember coming back to life and they were about to hit me with the paddles.

As I learned later, the paddles wouldn't have done anything for, you know, they're for arrhythmias. I wasn't having an arrhythmia. I wasn't having anything.

Brad Minus: I mean, that's just, I can't imagine. [00:20:00] So, you know, we can talk about that. We can talk about the intricacies of the Canadian health system versus the American health system. Some other time, but it doesn't sound too much different than some of the stories I've heard here. And, you know, our health system is different, but the same.

That's crazy. I mean, the idea that they found out what was going on and they still waited four days. You're literally dying. When was the next time that you're going to die and you weren't going to come back? That's what I'd be thinking as a doctor.

Fred Rutman: Yeah. And the doctor that did my surgery, it was his last, I was supposed to be his last operation before he went on vacation. So, you know, it's like, you never want to take the last flight out of the airport, because if that one goes down, you're stuck. And, you know, I don't know how, how much this guy was concentrating or not.

They ended up, I ended up having another incident on the morning. I was supposed to have the surgery. So they bumped me up a couple of slots. [00:21:00] They put me in ICU finally. And then I got the pacemaker and it worked great. Kept me alive

Brad Minus: for four more years. Oh, great. Good. So were you completely without incident for four years?

Fred Rutman: Yeah, the pacemaker replaced the electrical signals in my heart, and I was good for four more years. So, pacemaker, for those in the audience who don't know, it's a little supercomputer that's probably the size of an old style pocket watch. And depending on your medical condition, they run a couple of wires or leads through a vein that go into your heart.

And, it's an amazing, amazing device. If you think about only back in the 1950s when they were developing this, you were attached to an electrical cord.

Brad Minus: [00:22:00] Jeez. You know, it makes me think of the old Iron Man cartoons and the old Iron Man comic books. I don't know if you saw some of the older ones, but in the, way back when Tony Stark was like, he was, same thing, black hair, kind of a goatee type thing, but the heart that he has wasn't an infinite loop that they talked about the arc generator,

arc generator, whatever, that he has where it's, it's a redevelopment, you know, it's a, a constantly read a regenerating, energy source, right. And power, which is why there's sometimes when he's flying and stuff, but he's using more of the arc, the arc, the arc generator, then, then his body can handle and that's when he's got a, all right, get out of the suit, you know, recuperate himself and then he can go back and fly off.

But in the original comic books, it would, the, the, it would run out of a charge and in the frames you would see him like sometimes it would be too much and he'd be crawling. [00:23:00] To an outlet and he would go underneath his shirt and he'd pull out the cord and he'd plug it in just like in the 1950s what you're talking about.

So four years went by and you're good to go. Did you, in that four years, my grandmother had one and there was every so often she had to go get the batteries replaced.

Fred Rutman: Supposed to last 10 to 15 years. I made it four and then the pacemaker started to malfunction. You know, these things aren't supposed to fail, you know, occasionally they'll have a recall and the doctors will know, oh, we've got to take this out, but there was no recall for the pacemaker or my wires. And it turns out the insulation in the wires cracked, so it kept shorting out. So, when it shorted out, I shorted out because I'm 100 percent dependent on it.

So, what I went through in 2009, I went through again. In 2013. [00:24:00] So did they replace it? Yeah, they had to put in a new pacemaker lead, which didn't go to plan. I suggested to the doctors, you know, my battery drained prematurely because of all this shorting out. And everything I said, why don't you just put in a new pacemaker?

And again, I thought maybe this is something the doctors should have thought about. It shouldn't be the patient coming to them. Anyway, whatever happened. So the guy that was doing my surgery was a resident, wasn't the actual surgeon. And I wasn't very confident in this guy whatsoever for a variety of reasons.

When my first pacemaker was put in, they put you under completely. You know, general anesthetic for this one. They said, Oh, we're not putting you to sleep. You're awake. And [00:25:00] it's just like, we numb you, you know, just like going to the dentist or whatever, then we use the laser scalpel too. And, it was very uncomfortable.

I was having a bit of a panic attack, which I've never had before. And when my pacemaker shorts out, I know like I've got like a two or three second window where I know it's stocked before everything stops functioning. And I'm lying on the table and I'm looking up at this, I guess, scoreboard that's got all my vitals.

And I knew before it showed up on the, on the scoreboard that my heart had stopped again. And I just said, Oh, I'm gone. Also I coded on the table and all sorts of bedlam ensued. And then, they, they put these pacing pads on you before the surgery. So [00:26:00] those kicked in after about 10 seconds and revived me.

But then it's not like what you see on TV. It's pure insanity. You know, they don't have every doctor and everything that they need. And you know, people are screaming and swearing and everything. So, so they had to put in a temporary pacemaker, which they inserted through the groin and they didn't have time to freeze it up.

They didn't have time to sterilize it. So I could, I've definitely getting speared in the groin off my bucket list.

Brad Minus: Jeez. What a way to put that Fred. Yeah. Oh my God. I do appreciate the humor that you put around it. It's very funny. And it does, it makes it a little bit more, you know, palpable to some of us thinking all we go, [00:27:00] oh, we're thinking about us.

He died. He died. He died again. I mean, just the idea of it is just it's it's it's scary. And the fact that you went through it and the fact that you knew it was happening, that is, that's incredible. So did the, so they replaced, so the, now you've got an An art of, temporary, pacemakers.

So is this one now? Okay.

Fred Rutman: Yes. To a degree. I'm being kept alive by a nine volt battery that they have to change. Bless you. I think it was every 12 hours. So, the nurse comes in after I get back into my room, and she says, you know what? Not sure how much this was used before you got it, so I think we'll just give you a fresh battery.

And I didn't realize it was a 9 volt, so they're wheeling me back from the operating room to the ICU, and I'm thinking, how long is this frickin [00:28:00] cord? I'm thinking this has got to be plugged into something. I didn't realize it was a battery. And then probably 45 minutes after I get into the room, there's a power outage.

And I was like, Oh, just one thing after another. I mean, you can't make this stuff up.

Brad Minus: I couldn't, that's incredible. Well, you had a power outage, but luckily you were attached to a nine volt battery.

Fred Rutman: Energizer bunny,

Brad Minus: you're kept alive. So what was the, obviously, cause you, I mean, you died on the table, so they weren't going to start cutting into your chest.

What was the outcome there? Did you end up just recovering and then they went back and replaced the lead or how'd that work?

Fred Rutman: I had to wait, I think seven or eight days. The temporary pacemaker was put in so precariously under pretty dire circumstances, I was [00:29:00] on whatever is like eight levels above bed rest.

It was like, don't move. You can't roll over to go to the washroom. It was almost, forced paralyzation kind of thing. And on, the 10th day that they brought me in to try and do this surgery over. That was the first time I really advocated for myself. It was a whole new, surgical team.

And I told them, you have to do A, B, and C and D. Otherwise. I'm not letting you proceed because this was just horrific for me. And they did that and they couldn't install the new pacemaker lead. So I'm again, awake for all this. And they had to numb me a number of times. Cause I think the procedure ended up taking about three hours and 30 minutes.

It should have a normal pacemaker takes like 25 minutes. [00:30:00] They do 750, 000 of these a year. It should be pretty routine. And it wasn't, and I'd wake up and the doctor. I mean, I'd pass out just from exhaustion. The doctor would be on a video call or on a FaceTime trying to figure out what's going wrong here.

And they finally figured out how to get this new lead in there and they hooked me up and it was pretty good.

Brad Minus: All right. So you got five years out of that one. Yeah. Four years out of the first one, crack the crack, the insulation on the, on the wire, then had to go, had to go into and get that lead replaced because you started dying again, and screwed up.

Then they got back in there. They finally were able to figure out what happened and now you're good until 2018.

Fred Rutman: So then it was a combination of, you know, the battery was. Getting past its due date prematurely. [00:31:00] And, and the new pacemaker wire cracked as well. So we eventually found out from another doctor, a neurologist, that the entire vein that those wires are supposed to go through, it collapsed.

So we're not sure, you know, it's a chicken and egg. Did the wires crack because the vein collapsed? Or, you know, did they crack on their own and then the vein collapsed? It really doesn't matter. You know, fact is these, these leads crack and we're shorting me out. We had to do something.

Brad Minus: So it was the same thing that was going on that told you that you needed to go back in.

You started to just collapse again in multiple times. Okay. So this is something by this time you've recognized this.

Fred Rutman: Yeah. It's common for me, not for anybody [00:32:00] else.

Brad Minus: Those five years were pretty much incident free.

Fred Rutman: Until it started, the crack got so bad that it was obviously shorting out. And then I would short out stuff like that. So went back in and the surgeon figured out what was going on. Basically one of his colleagues, started pushing the pacemaker around externally and he'd push it in one place and I'd like, you know, and he's like, I can kind of see the problem here.

It's definitely a pacemaker issue. It's not a you issue. And so plan was that I was supposed to go in and they would put an entirely new pacemaker system in on the right side of my body and, you know, take malfunctioning stuff out as much as they could. And they ran into the same problem. They couldn't get the new pacemaker wire, threaded through into my heart.

So [00:33:00] before this surgery, I pleaded with the doctor, look, I've been dead enough. Like, I don't want to be awake for this, it's too much trauma. They don't like putting people under if they can help it. So, I really pleaded with them, and I said something along, I know you want to save my life, but if you kill me, I forgive you.

Like, just put me under, I don't want to go through this again. And that's what they did. It was, semi successful.

Brad Minus: Semi successful.

Fred Rutman: Semi successful.

Brad Minus: Mean?

Fred Rutman: It means I am now a member of the simultaneously functioning dual pacemaker. I actually have two pacemakers keeping me alive. I was told I was one of eight people.

They didn't take the one out on the left? No, they couldn't fully install the new [00:34:00] one. So I know what happened from my previous surgery and subsequent surgeries. My surgeon was on the phone. And FaceTiming with engineers and software engineers and whatever, trying to figure out how to keep me alive. So I went in, I think for noon, that's when the surgery started.

And when I woke up, it was 5 30. And that's how I knew something went wrong because I was under for a long time. I realized it should have taken 15 or 25 minutes. It didn't. So then the next day the doctor came to see me and told me he had to turn himself into Harry Potter and perform some wizardry.

That's how I'm alive. That's why I'm alive today.

Brad Minus: Oh my God. Did you, did some of this, [00:35:00] there had to be, so there's obviously other, other injuries, I mean, cause. Every time you died in, you know, before 2009. I mean, there'd be a few times when you cracked your head open. And so it was, it was there and you already, you know, had, had issues.

Fred Rutman: Further compromised from all the head trauma

Brad Minus: I can imagine.

Fred Rutman: So I'm Jewish and I'm fairly religious. We pray three times a day. And one of my rabbi friends brought me my prayer book and I've been learning Hebrew since kindergarten. You know, I'm not the greatest at it, but I can read the prayers.

And when I opened up. To the section I needed to, I realized I could no longer read Hebrew. All this head trauma had knocked an entire language out of my brain.

Yeah.

Brad Minus: And that language is hard enough. Yeah, I stopped trying to [00:36:00] learn. After, my 15th birthday, I went to Hebrew high school right after my thing, and I tried to go do conversational and it's hard enough. And then especially if you're doing script versus, full alphabet.

For those of you, the full alphabet vowels are symbols, consonants are letters. And sometimes you read in script and there are no vowels. You just need to know that they're there, so that's hard enough.

Fred Rutman: Can't, I still can't read in script. I can only read with the vowels, and I'm just now getting back to where I can keep up at the pace of the congregation for the prayers.

So it's been a long road. I had depth perception problems. I have balance problems. Not only can I not visualize, I had this to a degree before. I often don't recognize people, unless I know them very, very well. I've had times when [00:37:00] my neighbor would be walking down the street and I just wouldn't recognize her.

So it can make for some interesting yet awkward social interactions.

Brad Minus: Oh my gosh. So what were some of the, care plans? For those things that were going on between, I mean, concussions, you had to go through some concussions and post condition stuff there had to be going on and, yeah, I mean, some sort of, brain trauma that had to be going on as well, right?

Fred Rutman: I recognized it, but, you know, doctors can be very siloed. And so I was in a cardiac ward and that's what they were focusing on, cardiac issues. There was no thoughts given to any sort of treatment plan for my neurological issues. So it was, you know, up to me to figure things out, and thankfully I know that learning, [00:38:00] especially above your pay grade, helps your brain regenerate.

It's a big thing now that everybody's working on these things to regenerate, your neurons and things like that. But I think people have known this intuitively. Exercise and in learning and stressing your brain best path to recover and I intuitively knew that I started taking all sorts of courses.

Got a certificate in digital marketing and being 938 years old. I was definitely the elder in the class with all these 21 year olds. We're just zooming around and things got better. And my psychiatrist had been away on that leave. So she didn't know any of this was going on, and I didn't know if she was ever coming back from that.

Probably the day that she called me and said she was back, was one of the happiest days of my life. [00:39:00] Finally, someone I can talk to about this, and maybe get some semblance of treatment going. She's really good at her job.

Brad Minus: And this was after the 2018 incident or the 2013 incidents, what you're talking about when she left.

Fred Rutman: She left again, I think she came back in like 2012.

Brad Minus: Okay. So it was right before the 2013 incident,

Fred Rutman: she decided to have another kid and went away again for another few years. Yeah. Trying to find a psychiatrist that you mess with is almost impossible. Any sort of therapist that you mess with.

Brad Minus: Yeah. I'm glad you're alive, you know, and I think it's amazing that you could sit there and talk about that. I got two things I was thinking about. One is, [00:40:00] so the first, pacemaker where they lost the installation on the lead. When they went to go put the 2nd 1 in, in 2018, was it the same brand?

Fred Rutman: That's a great question. Because these medical device companies are all acquiring each other.

So, you know, the names change and unless you can see the serial numbers and stuff like that, I have no idea. I know you would get cards when you go to the pacemaker clinic and they'd say, you know, Abbott labs or Boston biometrics or whatever they were. Right. And, it was always a different name, probably could have been the same company.

Brad Minus: Yeah, I was just thinking, I mean, if the research was done to where, okay, the first time that this happened, they go back and say, oh, the Abbott labs pacemaker 1000. Oh, well let's check it out. [00:41:00] Oh, listen, there's numerous cases of the insulation, you know, being dissolved, dissolving and bearing out the wire, which then shorts the pacemaker, but maybe not as many with the cardiogenics 7, 000, you know, we should have put that one in there instead, you know what I mean? I would think that that'd be something that the doctors would be thinking about.

Fred Rutman: Yeah. There were no recalls on anything that we could find. And I'm, you know, I'm not the world's greatest researcher, but I can search for recalls.

One of my family members is. a legal nurse, and she works with malpractice lawyers on issues. And she couldn't find anything related to it. Lawyers she works with, and she probably works with about 60 or 70 of them, had never heard of anything like that.

In Canada, even [00:42:00] if you have a good case, like for me, if I wanted to sue, you don't win anything of substance, like unless you become essentially. in need of full time ongoing care for the rest of your life because you're incapable of doing anything or you die. Those are the cases where you'll get a payout.

Neither one really to you for any quality of life.

Brad Minus: Okay. So you have to die in order to get a payout. You're the guy that has, died over 22 times. Speaking of that, let's dive into that a little bit.

So we've talked about this, you've gone through, numerous. Times that you've actually died on the table. Now you've gone through several surgeries. The idea that you did absolutely 100 percent die. Now, first of all, you mentioned that, you knew that when you woke up that you had died.

And then you came to the point where all of a sudden you knew a couple seconds before. [00:43:00] Is there any, a time that, you can remember after that point that you died before you came back.

Fred Rutman: Yeah. There's definitely a few times. I've never had any of the, like, come to the light experiences that you often read about. And I, I don't deny that these people had those experiences. Because I think everybody's body is different and your death will be unique to you. So I didn't, it's almost, I almost feel ripped off that I died so many times, not once, you know.

So, but I definitely had a bunch of out of body experiences and one in particular was it stuck with me and I was riding my bike to synagogue and I was going through this park, which. Oddly, it was right beside a Jewish cemetery and, and my heart [00:44:00] stopped and I just, you know, I'm in the middle of nowhere.

It's not a well traveled path. It is in the day. Kids go back and forth to school, but at night nobody comes by. So if I hadn't had my body revive itself. That's my final resting place. So I remember having the auto body experience, and I'm looking down on myself, and I'm tangled up in my bike. So I just, You know, conked over and I'm feeling very agitated and very uncomfortable.

It was almost like I was in some sort of spiritual tug of war. My soul was trying to leave my body, but it really didn't know, you know, should I go up? Should I go down? Hoping it would have gone up. It's like, and the body's trying to pull it back in. And, and, you [00:45:00] know, there's a lot of frustration and a lot of anger and just being very agitated.

I guess, you know, obviously it wasn't my time to go, so the body won that tug of war, but it made a mark on me, I wasn't always semi religious, but I've always believed in God, and people often ask me, you know, are you more religious now, or do you have a deeper faith in God or anything? No, no, I don't think I'm one of those people that said, you know, please God, if you keep me alive, I'll do this and I'll do that and I'll shovel the neighbors you walk and all that.

I didn't have any of that, but I think it was also partly because I was so battered from all these experiences. I was just trying to focus on moving my life forward.

Brad Minus: Do you think that maybe the struggle was. Like you said that you had [00:46:00] this, you have this deeper faith in God. Do you think there was a, there was a point where You were like, Oh my God, I died again.

I'm so done with this. That may be the struggle to maintain the, or continue where you were going forward, in other words, dying, was. And God was the one like, no, no, no, no, no. You need to go back. You know, maybe you were, do you ever feel that way? Yeah. Well, no, I'm, I'm feeling like, like, Hey God, this has been, this is like the 52nd time that I've died.

I think you're trying to tell me something. Let's just call it quits. And that's God saying no, no, no, no, no, no, no. You've got more to do.

Fred Rutman: Well, I think that everybody has a resilience gene that you're built in from birth with a certain amount of resilience for whatever situations you face.

And I also think it's, there's a resilience muscle and the more you work it, the more resilient you can become. And [00:47:00] I think watching my parents struggles as I was growing up, my dad had horrible, horrible arthritis. He was in unbelievable amounts of pain for most of his adult life. And my mom struggling with what she was struggling with.

You sort of learn it by osmosis. I mean, you know, my parents weren't saying, this is how you be resilient, but you sort of see it, and it's churning in the background, and I think that's a big part of why I'm still alive. Also, the communities that I'm in, particularly my Jewish community, I mean, the people that took care of me were just amazing.

You know, they take me to doctor's appointments and visit me in the hospital and add prayer vigils and, cook me meals. And part of the reason I wrote the book and started the podcast is because I wanted it a bit of a tribute to all these people [00:48:00] who've made a big impact on my life.

People are willing to help you, but you have to be willing to ask.

Brad Minus: That is an amazing message right there, Fred, and I appreciate you saying that. My parents both just went through something, in, July and August, and they live in a 55 and older community, it came to the point where my mom was in the hospital and my dad wasn't and then he ended up with COVID at home without my mom.

Their neighbors rallied around and sometimes they would stay with them, they would cook meals, bring them food, made sure they got up and brush their teeth my mom ended up, fracturing her sacrum. So when she finally got home after rehab, she couldn't get off the toilet.

She can get on it, but she couldn't get off it. She needed people to help her. And then my dad ended up in the hospital. So it was just a really, really bad time and for both. And of course, they sent me on a 12 day [00:49:00] cruise. They wouldn't let me not go on the cruise.

I was like, no, I'm going to stay. They're like, no, no, no, no. Do you know how much that costs? We were supposed to go together and they had the insurance, but because they were husband and wife, the insurance, you know, would kicked in for them, but they didn't do it for me just because they were my parents.

So they couldn't get the money back for me. So they were like, no, we'd rather you go and have that experience. We'll figure it out, you know, and they did, but it felt horrible. And when I got home, that's when I kicked in, but you're right, neighborhoods, as you get involved with your community, like you said, and I think that's something that people should, embrace.

That you know what? Those people will be there when you need them and you will be there for them. If they need you, we found that recently here in Florida, because we had Helene, you know, Hurricane Helene and Hurricane, Milton. And people all over the [00:50:00] place are going into neighborhoods that, you know, and with our neighbors that had big trees that they need to get off their lot.

And they had a board up, you know, beforehand they had to board things up. And then people had, we had people with water in their homes and neighbors are helping them, like, get some of the water out, moving out their stuff onto the yard. So, I love that. And I love that you were talking about that because I think that's something that, you know, that was very prevalent in the sixties and seventies.

You always knew your neighbors. You had block parties, you know, in the whole bit. And even in the eighties, but somewhere later on, all of a sudden it wasn't. You know, it wasn't something at least here that you notice people started, you know, spending more time in the house, not meeting their neighbors or anything.

So, that's a great message there. You've written that, 450, 000. Americans, Canadians die from medical errors yearly, which I guess is a through line for your podcast. So as far as [00:51:00] your pacemakers go, do you believe that, you know, a lot of that, that there was medical error there?

Fred Rutman: I don't think there was medical error. My current pacemaker surgeon, as I said before, is a wizard. And he had to do another wizardry on me, almost. A year ago, because the batteries were running out again. So, I think some doctors, not everybody can graduate at the top of their class. And some doctors obviously weren't at the top of their class and some nurses weren't, but the majority were, you know, they brought their A game and they were compassionate and they were helpful and everything.

It's just, I don't know, against the odds, like I wish, I could beat [00:52:00] these odds with a big lottery.

Brad Minus: Everything's okay now.

Fred Rutman: Everything's okay until, I need another battery swap. I went to get my pacemaker checked a few months ago, and I don't know if you can see, but like there's this huge. Oh yeah. So it's not supposed to be like that. It's supposed to be, you know, barely noticeable.

Brad Minus: Right, right.

Fred Rutman: Like this one is. You know, you can feel it, but it's not sticking out. So I said to the surgeon, why, why is it sticking out so much? I thought after the surgery it was sticking out and I thought it was just all swollen and everything. He says, well, you know, it's kind of sitting on a landfill. You know, with all the other junk they have to leave in there.

Brad Minus: So that's why our tissue builds up

Fred Rutman: well, old wiring and extra wiring.

Brad Minus: Oh man, [00:53:00] that's, that's just horrible. It makes me feel like you're the reverse of the bionic man. You know, those wires did something. You've got stuff in there that doesn't do anything. Oh man. I'm sorry to hear that, but, I'm glad you're alive and you're, And you, I mean, you look healthy.

And I know that you're a big proponent of, of, intermittent fasting.

Fred Rutman: Yes.

Brad Minus: Where did that start?

Fred Rutman: That started with seeing my regular cardiologist, not the pacemaker cardiologist. I was just going for a checkup and I was in the exam room and he walks in and he throws this book at me and he says, buy this, read this, do this, but only after you talk with like your other six primary care doctors.

The book was the obesity code by Dr. Jason and he's a nephrologist kidney specialist here in Toronto and he started getting his [00:54:00] patients to do intermittent fasting.

And he was tired of people losing limbs from diabetes and kidneys from diabetes and going blind. And he was seeing once you got people intermittent fasting and their sugars would go down, all these other things in their body would also start to heal up. And he's having tremendous success. So, I started it and I eventually through, my work wife, Risa, she found me an intermittent fasting group on Facebook.

And, like, why didn't it occur to me to look for intermittent fasting groups on Facebook? There's a group for everything on Facebook, right? And I fell in love with this group and I eventually became a moderator in the group. The group was run by a woman named Jen Stevens. She wrote the forward in my book and, when you're a moderator of a group of [00:55:00] 350, 000 people.

There aren't too many questions you don't get asked. Some of them I wish I wasn't asked. And I've just seen so many people heal their bodies, beyond weight loss, that, I'm a full proponent of intermittent fasting if it's safe for you.

Brad Minus: What kind of results did you see

Fred Rutman: well, I was diabetic.

So I was on insulin and within six months of intermittent fasting, I was off insulin, like six months. Now your mileage may vary. I mean, all our bodies are, you know, unique, but, I had sleep apnea. It went away. I had asthma. It went away. Generally my body aches, like every joint. In my body, and I attributed it to being, you know, that I had 340 pounds at one point.

I played football, I [00:56:00] played hockey, I played rugby in college. My body was just beat up. Probably three months in, the pain started going away. So, this started, I started fasting in 2018, summer of 2018. What are we? Six years later, six and a half years later, I don't have an ache or pain in my body.

Brad Minus: Wow. And now that I have not heard, I'm a proponent of intermittent fasting, myself.

I train people to do Ironmans and marathons and ultra marathons and all these crazy things. Right. And I do have people that, you know, for nutrition wise. So we divide things up between nutrition and fuel.

There's nutrition, which is everyday nutrition and then fuel is, pre workout during the workout and post workout. Right. So, and I have done disproponency where, you know, do an, I've got some people that do an intermittent fasting on light days, [00:57:00] on rest days and yeah, have gotten great results, you know?

None of it was more pain. Some of it was more, carbohydrate, efficiency. So by regressing, releasing the carbohydrates, right. When we're in nutrition phase, we're not working out, when you add them in for training, because your body's not consistently utilizing them when they're not training.

When you do add a sufficient amount of carbs, when you start training, they're used a lot more efficiency. You get a lot bigger of a boost, when your carb line is not like constantly like this, right? You eat a banana, then it comes up, then it comes back down. You eat a candy bar, it goes way up and falls right back down again.

Intermittent fasting, which, you know, like you said, Keeps your glucose line pretty straight. Found that as my athletes are at work or they're with their kids they're getting this nice and even, and then when they go to training, [00:58:00] they can use the carbs and the carbs last a little bit longer, because they're being used efficiently, the body realizes that it doesn't need to take it all at one time.

It's pretty amazing. I didn't know about the pain part. So that's really interesting.

Fred Rutman: It's all a hormonal thing. So I can go into it a little bit. You'll tell me if I'm going too deep, but what it really starts to affect initially is your insulin levels.

So your insulin is basically pumping 24 seven, but if they're telling you to eat six times a day or seven times a day, your insulin levels can get too high. It's like you have a pool and you're overfilling it. And once your insulin levels get too high and stay too high, it affects almost every other hormone in your body.

It elevates your cortisol levels. It messes up your leptin and ghrelin, which are your hunger and satiety [00:59:00] hormones. It messes up your gut biome. And it's one of the key things that hardens your arteries. If you have perpetual high insulin, your arteries will harden regardless of your diet. It also, will show elevated levels of growth hormone.

When you fasted for an appropriate amount of time, your brain derived neurotrophic factors to help your nerves regenerate and all that stuff. It's just a cascade effect. It heals your leaky gut. It just goes on and on. And most of the doctors, Don't know about it. They take their three hours of nutrition in mid school and then their advice to you is, eat less, move more and your body doesn't work like that.

We're not an equation.

Brad Minus: I know I get that. And yeah, and I'm a proponent to what works. [01:00:00] And, you know, some people doesn't work. And in my, you know, it's definitely, You know, I got definitely people that, don't feel as good on an intermittent fasting as a lot of other people and then I've got people that are, big keto.

And it works for them and not for a lot of other people. So, you know, you've got to find the strategy that works the best for you. But wow, What a rollercoaster we just been on, you know, we talked about medical error. We talked about, near death experiences.

We talked about the heart. We talked about, pacemakers and how they work. Now we talked about intermittent fasting. If you can't find a nugget to get you motivated out of this episode, I have no idea where to go from here. I have Fred here. That's died numerous times. And is here to talk to you about it.

And he's given all these wonderful pieces of information. So this has been an education, Fred. I can't tell you how freaking grateful I am to you. Fred has, the dead man walking podcast. And when do [01:01:00] you release usually?

Fred Rutman: Generally on Wednesdays. Okay. I'm a little behind because, yeah, of the Jewish holidays and things like that.

Brad Minus: Okay,

Fred Rutman: yes,

Brad Minus: Okay, great. And you just said you had that you had, you got Facebook groups that you run. So I'm assuming that you're also, you're also, you're on Facebook, probably pretty active.

Fred Rutman: Jin closed down her Facebook groups because Facebook was doing Facebooky things.

So apparently the word fat became illegal and they would shut. So you can't talk about. Breaking down fat, anything it said, the algorithm saw the word fat, you were fat shaming, and they would put you in the penalty box and you just can't operate that way.

Brad Minus: Yeah, that's what, so are you, did you find yourself more on Instagram then?

Fred Rutman: I'm on Instagram a little bit. I usually post, when I've released a podcast or I've guested on it. Not as [01:02:00] prolific as some of the cat people.

Brad Minus: I get that. I totally get that. And then I guess you're on Instagram as well. And then, of course, the book that is already, published, and we'll make sure that we have a link to that as well.

The summer I died 20 times. Oh, that's a sitting with the editor.

Fred Rutman: Is that that one

Brad Minus: published the summer I died published. Okay. So the summer I died and we'll edit that part out. So he out on Amazon, the summer I died 20 times. Times by Fred Ruppman. Okay, and he's in the middle of his sequel and I guess you're calling it dead again. And so we'll be looking out for that And then we'll definitely have all of your socials linked up in the show notes We'll have a direct link to the Amazon to get your book, which I, I'm very, very interested in reading.

And he's also been on numerous other podcasts so that you just have to take a look, you know, do the search bar [01:03:00] for, for Fred Ruppman. What is that repeatedly dead Fred? Yes. Yeah.

Fred Rutman: Indiana gave me that name one day.

Brad Minus: That's hilarious.

Okay. It's not. I mean, it's funny because it it's yeah, because it's. Yeah, and that alone. It is funny. But yeah, so this has been the information that came out of this episode is ridiculous and, definitely, you know, I would listen to this a couple of different times. So definitely we'll have all the socials hooked up.

We'll have the book, we'll have the podcast, all that's going to be in the show notes for you. Plus, of course, as I always do, I always give you takeaways. Takeaways are always in the notes. So yes, again, Fred, thank you so much. Can I leave one takeaway? Absolutely.

Fred Rutman: So there's a gentleman named Victor Frankel. He was a Holocaust survivor, psychiatrist, renowned, and he wrote a book called man's search for meaning. And in that, and I'm paraphrasing [01:04:00] here, he says, if you have hope, you can conquer almost anything. Hope is free. You don't need a membership to hope. It's not part of our broken supply chains or anything.

Have hope, have faith. It'll get you through a lot of things.

Brad Minus: That is probably the best message ever, especially in this day and age. So thank you for that. I think that's huge. For the rest of you, If you're watching on YouTube, please go ahead and, hit the like, subscribe, hit the notification bell.

So you always know when a new episode is dropping, if you're on Apple or on Spotify, please leave us a review and it doesn't have to be a good review. It could be a bad review to give us a good review. on how I can make this podcast better. But I would just love to get that feedback from you.

And of course, if you have any ideas, if you've got any friends that, fall in line with the scope of the podcast, that'd be great. Let's send them my way. But other than that, thank you for watching, [01:05:00] listening, and we will see you in the next one.