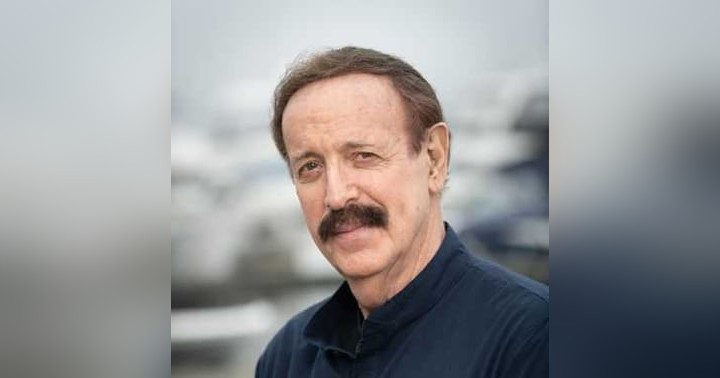

In this episode of Life-Changing Challengers, host Brad Minus welcomes Dr. Alan Weisser, a chronic pain mastery expert, clinical psychologist, and former trial lawyer. Dr. Weisser shares his extraordinary story, from overcoming a life-altering injury at the age of 12 to developing a unique method that empowers people to thrive despite chronic pain. Through personal anecdotes and professional insights, Dr. Weisser highlights the transformative power of resilience, perseverance, and recognizing one’s untapped potential.

Dr. Weisser also discusses his Seattle-based practice, where he and his team help individuals optimize their innate potential through psychological and existential approaches. Whether you’re dealing with chronic pain, emotional struggles, or seeking inspiration to overcome life’s challenges, this episode is packed with wisdom and actionable advice.

Episode Highlights:

- [1:00] – Dr. Weisser’s childhood in New York, his love for science fiction, and early formative experiences.

- [4:00] – A life-changing diving accident at age 12 and the journey of recovery that followed.

- [10:00] – How negative self-talk and societal expectations shaped his self-perception as a teenager.

- [16:00] – The chemistry teacher who believed in him and ignited his academic turnaround.

- [24:00] – Transitioning from a trial lawyer to clinical psychology and finding his life’s purpose.

- [40:00] – Developing the “existential immune system” and empowering others to reclaim their lives despite chronic pain.

- [55:00] – The importance of mindset, resilience, and embracing life’s challenges as opportunities for growth.

Key Takeaways:

- Challenges Are Opportunities: Life’s setbacks are a chance to uncover hidden strengths and potential.

- Perseverance Pays Off: Consistent effort and determination can overcome even the most daunting obstacles.

- Reframe Your Pain: Chronic pain and emotional struggles are part of the human condition, but they can lead to transformation when approached with the right mindset.

- Empowerment Through Truth: Acknowledging negative realities is the first step toward empowerment and reclaiming your life.

- Human Potential is Limitless: Every individual has the innate capacity to thrive, no matter the circumstances.

Links & Resources:

- Dr. Alan Weisser’s Website: PainMastery.com – Learn about his methods and connect with his practice.

- Follow Dr. Weisser on LinkedIn: Alan Weisser, PhD

- Recommended Book: Awakenings by Oliver Sacks – Mentioned during the episode.

- Dr Weisser's Book: New Possibilities: Unraveling the Mystery and Mastering Chronic Pain - Get it on Amazon

- Contact Dr. Weisser: Schedule a consultatio

Have an idea or feedback? Click here to share.

Contact Brad @ Life Changing Challengers

Instagram: @bradaminus

Facebook: @bradaminus

X(Twitter): @bradaminus

YouTube: @lifechangingchallengers

LifeChangingChallengers.com

Want to be a guest on Life-Changing Challengers? Send Brad Minus a message on PodMatch, here.

Brad Minus: [00:00:00] And welcome back to another episode of life changing challengers today on the show so excited. I have got Alan Weiser, Dr. Alan Weiser, and he is a chronic pain mastery expert, which includes him being a clinical psychologist and he deals with. chronic pain and suffering. Now, just to let you know, it says PhD at the end of his name, but he's also is a JD because he started as a trial lawyer. So we're going to talk to him, but he has a practice in Seattle, Washington, where they designed a unique method to optimize a person's innate potential. And that helps them become empowered and thriving, even with suffering from chronic pain.

So, Alan, how you doing today? I'm good. Great, great. So, Alan, can you tell us a little bit about your childhood, [00:01:00] where you grew up, maybe what was the complement of your family, and what was it like to be Alan as a kid?

Alan Weisser: Okay. So, initially, I grew up in the Bronx, in New York. So about the age of eight and then the family wanted to move out of the Bronx, it was changing.

So we moved out to Queens, I was there until I was about 12, and then we moved out to Long Island to an area called Port Washington. And so that's kind of where a lot of things really happened, although there were events that led up to it. If I think back, cause we had a little bit of a discussion and I'm thinking back to earlier experiences before the big one.

So, I would say the formative years really were mostly on Long Island, growing up. Yeah. You have brothers and sisters? Two brothers. One has passed away from cancer. The other's an older brother. No sisters. Yeah, no sisters.

Brad Minus: What'd your parents

Alan Weisser: do? My mom was an interior designer. [00:02:00] My father was a public school teacher, which actually has a lot to do with what I do.

Really?

Brad Minus: Well, that's going to be interesting. I guess we're going to, we're going to find that out in a little bit. Were you active in any sports or anything?

Alan Weisser: I wasn't an athlete, but I played in sports. For me, it was mainly fun. I wouldn't say I practiced a lot. I just took a game when I had a chance.

Brad Minus: Okay, like Sandlot?

Alan Weisser: Yeah.

Brad Minus: Did you play stickball?

Alan Weisser: I'm glad you mentioned it. I was about to say that stickball was my favorite thing.

Brad Minus: I love it. I love it. Cause you just don't hear that anymore, right? You know, everything's baseball, this and baseball that no one ever talks about the old stickball. I can imagine.

I can imagine. Hey, real quick. It was, did you usually use a tennis ball in stickball?

Alan Weisser: I don't remember. I don't know. Maybe.

Brad Minus: No problem. I was, I was always curious, you know, because when, growing up, if you're playing Sandlot, baseball and you use the [00:03:00] league ball. So I was always curious about that. So what'd you do for fun?

Alan Weisser: I guess the question would be, what was I doing that wasn't fun?

Brad Minus: I love it.

Alan Weisser: You know, I was just, I was a curious, imaginative kid. So. I was always looking for things to get into, things to do, things that were interesting, things to learn, especially the things to learn about. So I was very good at entertaining myself. I love science fiction and cartoons. I even do a form of cartoon art.

Brad Minus: Oh, really? Okay. That, that, that I did not know.

Alan Weisser: Well, actually, the first book of that art will be coming out in 2025.

Brad Minus: Oh, fantastic. Fantastic. Yes. Because what I didn't mention is that you're also an author and we'll talk about that a little bit later as well. But from what I understand, and my research has told me that something very detrimental in your life happened.

What about the age of 12? 12 and a half. [00:04:00] Want to tell us about that?

Alan Weisser: Oh, yeah. So we're living in a nice upper middle class suburban community on Long Island and we belong to a community pool. And this is emblematic of me as a child. I'm one of those people, if I get interested in something and I want to try and figure it out for myself, you know, taking lessons, sure.

But I have a hard time committing to that with some exceptions like martial arts. So, I decided I wanted to be able to do a backflip on a diving board, looked pretty cool. I didn't know how to do it, but I figured I could figure it out. So, I tried my first backflip. Did you know when you do a backflip, you're supposed to dive out from the board, not straight up?

Yeah. Yeah, so I came down on the board, I broke my neck in two places. Ouch. Long story short, I mean, I was taken to the hospital, it was a long time ago, keep that in mind. So, they got me in the hospital, I know I broke my neck, I've got a cast on, right? And the doctor comes in for the first time, [00:05:00] and keep in mind my first exposure to a doctor outside of the family doctor, who is like a family friend.

He comes in and he says to me, first thing he says to me, If you don't die, and you're not paralyzed, you will be a cripple for the rest of your life. Yeah.

Brad Minus: At 12 years old?

Alan Weisser: 12 and a half. 12 and a half.

Brad Minus: That just the fact that your parents allowed that to happen.

Alan Weisser: Well they didn't, they weren't there. They didn't know.

Brad Minus: Oh, they weren't even there yet.

Alan Weisser: Oh no, no, this was just me and the doctor. Oh, yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I even call friends to say goodbye.

Brad Minus: Oh my god. So, as it was the most, probably one of the most affordable, affordable thing, can you tell us, what were you feeling at that point? So, you're in this bed. Can you move?

Alan Weisser: I can move.

I'm not actually paralyzed but there was this possibility I could be, you know, because of the damage. The part that I did not remember, this is [00:06:00] incredibly important. I didn't remember this until maybe Seven or eight years ago, working with a patient and talking about this story, because that story is useful for people.

I remembered something that I had never remembered before. Keep that in mind. Many, many, many, many years went by and I had not remembered this. When he said what he said to me, I thought to myself, stupid, stupid, stupid, look what you've done. Now keep in mind that I blocked that for years. But here's the flip side.

I almost flunked out of high school. If I hadn't run into a certain chemistry teacher who I was headed towards flunking out, going to Vietnam, probably dying. But the point is, if you'd asked me in high school why I wasn't doing well, I would have said I'm stupid. I would never have made the connection.

Brad Minus: So basically what you're saying is that you started negative self talk at that [00:07:00] point and it just became a habit?

Alan Weisser: Yeah. It completely undermined my confidence, but the problem was I wasn't allowing myself to know what I was thinking and feeling. If you talked to me during that time, I was in the hospital over a month. And I made so much fuss and mess that they had to send me home. And then I'm home on my back in a bed for a year.

Not allowed to get out of bed or even move around. But the whole time that I'm going through this, if you talked to me, I'd be cracking jokes and I'd be seeming like I'm fine. Nobody had any idea how frightened I was. Nobody had any idea how angry I was. All of that just kept to myself. Be a good stoic guy, right?

And that, that really goes to the psychological, the sociological advent of the times, right? I mean, back then, guys were told, and I mean, and I know it was back then, because it was when I was a kid is, no, if you're [00:08:00] a boy, you don't cry. You don't show your emotions, you don't remain vulnerable, you are uber macho, this is how guys are.

And if you didn't act like that, if you were in school, you got, you got teased.

Yeah, still true. So, that's the beginning of, a lot of this is learned from that moment forward. So we're sort of going forward and then backing, but that was the beginning as I eventually came to understand the existential impact.

You know, I'm just focused on recovering from a broken neck. I am not focused on any collateral damage in my life, you know, to be cut off from being in school at that age and then even going back to school and trying to get into a normal routine. There were tremendous adjustments and adaptions, none of which I paid any attention to other than to just persevere.

You know, if there's anything that, that is a hallmark of my attitude towards life is its perseverance. [00:09:00]

Brad Minus: And yeah, and you have but I'm curious as to, first of all, in that first year, with, to, to your, to your recollection what was like a typical day like?

Alan Weisser: Typical day was terrible. I couldn't get out of bed, and I was very restless.

I was afraid to do any of this. I had a brace on, but they led me to believe that I was that fragile. So I got very good at something that I'd already figured out earlier on in my life, and that was compartmentalizing. You know, one of the advantages to escaping into fantasy and science fiction is, you know, I have a sort of leave and be someplace else.

Yes. I spent a lot of time someplace else. I found, I found ways to be entertained but like I said, not paying any attention to the rest.

Brad Minus: Interesting. Did you after I guess the first year, maybe you can let us know a little bit more, but did you get to a point where you're going to rehab?

Alan Weisser: Nope. [00:10:00] Well, a little bit.

I actually had to go through rehab because my legs were atrophied from all that laying in bed. So I went through a certain period of time, actually there was more pain in getting my legs back in good order than there was from the broken neck. You can imagine what it would feel like to walk on legs that haven't been used for almost a year.

Yeah, no, and I, my new, miniscule, miniscule, I have that ability because I, I also had, I had an, a back injury that put me on my back for a little bit, but, but I'm an endurance athlete. So to go back and then for you, it was using your legs for me. It was trying to get to run again. But so it's just a tiny bit of what you felt.

Brad Minus: Probably. Maybe a hundredth of what you felt but I, I do, I have a little bit of a connection there. Which is how I got to be a coach, by the way, is because of that injury, almost the same way that you became, you know, what you're doing today helping people suffering from chronical chronic pain.

[00:11:00] So, so you really. So did you have any, like, real pain in your neck during that time?

Alan Weisser: I probably did, but I also figured out

how to deal with that. Block it out, yeah. Yeah. I can, I can see that. Cause sometimes it, sometimes when you as far as what I've been told is you could, if you damage the nerves enough, it's not the fact that you, that you actually have pain.

It's just the fact that everything's numb.

Yeah, no, I said my recollection of it's interesting. I don't remember much about the pain with my neck I remember my legs a lot more than my neck. Oh, but yeah, but the good news was you know during that year I wasn't gonna be paralyzed that seemed to be obvious Right.

I would be able to walk. But the idea that I was fragile did not go away. You know, as I, as I took the brace off and we got back into having me start to make movements, I was afraid to even just do that. Because they pretty much led me to believe that it wouldn't be that hard to have a real

problem. [00:12:00] So, your envision of yourself was your glass.

And anything that

you

might

do. I'm glass and I'm stupid glass, right? And remember, before that I was headstrong and I was willing to take anything on. I was by definition an explorer. I wanted to be a Magellan. You know, sail around the world. See if the world's really flat. And after the accident, all of that was gone.

So how long was it till you got regular use of your legs again?

I would say within two or three months. Of? Of getting back into actually walking and working on it. and get it back into shape. But, once again, I had to proceed cautiously. It's not like I get out there and start working on a treadmill or running.

Brad Minus: Right. Right, right. Well, no, no, absolutely. You know, you see that, you know, there's been plenty of documentaries on people having to relearn how to walk and gaining that stuff back. And it's a slow, slow process. So, I guess my question was, is that, so, you were a year in bed [00:13:00] and then you started to go to rehab and learn to walk again?

Alan Weisser: Yeah, they didn't want me out of bed or moving around for that much.

Brad Minus: And you're saying that so basically a year and a half after the accident was until you could, until you could have regularly, regular use of your legs again? Pretty much, yeah. Oof. So that brings you to like, what almost 14, about 14.

So you'd be heading into high

Alan Weisser: school, middle school,

Brad Minus: middle school.

Alan Weisser: Okay. Yeah, that was tough. Like I said, I wasn't the same person coming into this that I would have been. And it happened at that moment. That's so transitional for children, you know, that age we began to establish who you really are and whoever I really was, was gone.

At least I thought it was, turned out it wasn't, but for the time it was.

Brad Minus: That's an interesting, that's an interesting anecdote right there. I'd like to find out. So you get through, you get through middle school. And you, [00:14:00] do you find, you find yourself kind of like oddball out because of what's going on inside your head?

And

Alan Weisser: yeah, and I tended to sort of set my sights on hanging out with people who. I didn't feel the pressure to be anything with other than just me. I, I, I focused on other things. I, for example, I got into singing and putting together some singing groups. I had a doo wop group in high school. Nice. Oh yeah.

Brad Minus: I do those things myself.

I was, I was a semi professional actor and I loved musical theory for about, for about 12 years. So yeah, so I,

Alan Weisser: I focused on that cause I could be good at that. And I also focused on girls because I could be good at that too. So that was, as far as I was concerned, that was who I was. I was going to be in a singing group and a guy who could get along well with girls and that those are my strong points.

Smart? No. Otherwise talented. Nah. Like I said, huge [00:15:00] transformation in my sense of identity, which I was not aware of.

Brad Minus: So interesting because we're going to talk about your formative years. You're talking about, you know, high school and you basically what you're telling me is that you're focused on singing and girls.

And, but you also have been something earlier that you weren't a good school. You weren't a good student, but yet you met a chemistry teacher that kind of changed things for you. How do you want to tell us that story?

Alan Weisser: Yeah, so, I'm going through high school, I get to junior year, and I'm going to be flunking out.

I'm pretty much failing all my courses. And just keep this in mind, nobody seems to be paying attention to this. You would think family would have gone like, what's going on? Didn't happen. There's a whole other story to that. So I get to this chemistry course, and, do you remember Soupy Sales? Yes!

Brad Minus: Oh my God, I haven't thought about that in ages.

Alan Weisser: Yeah, well, I'm a big fan, but picture a chemistry teacher who's like Soupy Sales. So, young guy, very [00:16:00] funny. He loved to blow things up just to be funny. So I really like this guy. I can relate, right? And about three months into the semester, he calls me in after class and he goes, You're failing my class. Why are you failing?

I wish I could have videotaped this conversation. I said, because I'm not very smart, he goes, Yes, you are. I go like, No, I'm not. Yes, you are. No, I'm not. I mean, we went literally went back and forth. He goes, You know what? I'm going to tutor you personally. So he personally tutored me. We developed a real friendship and I got a C in chemistry.

That may not sound impressive, but trust me, it was what it taught me was this. I might not be smart, but if I worked really hard, I could do well, right? That began to sort of Yeah. shift my sense of what I was capable of. That carried me all the way through law school, college and [00:17:00] law school. This idea, don't have to be smart, just work really hard.

I developed a study system that would make you throw up if I told you just how much I put into it. But it worked. I even have taught it to people how to do that.

Brad Minus: That would be another book that you could write probably for the college students of today. I, I was not the greatest student either in, in high school either.

So I mean my first, I literally had to almost redo my whole freshman year. And it was more, cause I, my dad would tell you that I had gotten his street smarts. Like I could get around in the world. Put a book in front of me and, and tell me that I need to study this and I'm going to do anything but.

Brad, you're breaking up a little bit. I don't know if you can hear. Oh, no, I don't. I mean, I can't tell on your side. That's all right. All right. Yeah. And I just my dad would just tell me that I was street smart. You know, that I, I didn't [00:18:00] have this intellectual ability to grasp things off the page. I could hear it in class and I could take notes and I'd be fine and I could probably relay it back.

But as far as sitting down with a book. And later found out, not until I was 40, I found out that I had ADD and I just needed a different way of looking at it. But, but just like you, it was when I did need to get things done, it was hours and hours of study versus my friends who could read it off the page, get it, you know, take a couple little highlights, do a couple little highlights things and they'd remember it.

But me it was either I needed to hear it and actually do something with my hand. But I couldn't just get the knowledge off the page. So I get, I get where you're talking about. So, so you graduated and this chemistry teacher seemed to put you in the right direction. So you, then you, so you did end up being accepted to university.

Alan Weisser: Yeah, just a quick footnote. Because we were talking about who I am and, and how I developed as a [00:19:00] person. This is really the hallmark of everything I do. And that is that there, from my point of view, There's no such thing as a negative event. Any event, whether you like it or not, is an opportunity. You know, so I went sideways and I started singing, which maybe I would have done or maybe not, and formed a singing group, which was pretty good, and eventually got offered a record contract years later.

Brad Minus: Oh, nice.

Alan Weisser: Not a bad adaption, right? The artwork that I did as a child turned into an art form, which has been in galleries, and now I'm gonna put out there in books. It's so I set me the essential me was still operating looking for some place to express some way to express the potential that this is the thing that I've come to understand that human potential cannot be undone.

It cannot be stopped. You may tell yourself you don't have it, you may talk yourself into helplessness, but that is not the human condition. And my whole life, if I think about it, has been representative of the fact that I always [00:20:00] look for an opportunity no matter what goes down. And even, you know, that chemistry teacher.

taught me a lesson about how important one person can be in somebody's life. He changed the direction of my life because I came out of that going, well, just work harder and you'll get through high school. And I did. I had to go to night school for two years in order to get into college. I couldn't just go directly to college with my grade point average.

But fortunately I met the second most important person in my life at that point, a woman I almost married who, like my chemistry teacher, believed in me. And no matter what kind of negative self talk I wanted to throw in her direction, she'd just go like, that's not who you are. So that helped to continue to build my confidence and self awareness, got me through college.

And then law school, you know, you'll laugh if I tell you this, you know, you're 880, I'm dyslexic. So don't ask me to spell things. In [00:21:00] order to get into college, I actually had to take an English remedial class. in order to get into law school, right? I'm not even sure I would have made it if not for the fact that my brother had already gone through that law school.

But I did, and I was one of the few people who actually graduated, and one of the only people that actually passed the bar the first time.

Brad Minus: Wow, yes, I've heard that. I've heard that at the bar exam that there's a huge percentage that don't get it the first time. Oh yeah,

Alan Weisser: absolutely. And believe it or not, some of the same things I had to deal with when I had my broken neck came to play because I literally shut the doors to my apartment for six weeks, turned everything off, never left the apartment, spent 10 15 hours a day studying.

That's why I got through the bar exam the first time around

Brad Minus: and you know what I do have a friend who is a Lawyer who who is very smart did do very well Graduated, you know with honors from Loyola University and still did four weeks [00:22:00] of that exact same thing She closed everything off. She told everybody she said even even her boyfriend who she ended up marrying She goes I'm not talking to you for the next month.

You know, we'll talk on Sundays between 9 and 11 to say hi, see how things are going. But other than that, I don't want you contacting me. I don't want you saying anything. She told her parents that, you know, she made a deal with her parents. Her parents would leave her food by her door. She says, I'm not leaving this, except go to the bathroom, hygiene and take a walk every once in a while.

She goes, other than that, I'm not leaving the room until I've mastered this. Yeah, she did the same thing. She did it the first time and was like crazy score. But even her who didn't have our disadvantages Still, you know, did that exact same, you know, that exact same persistence, you know, determination got built in.

So,

Alan Weisser: well, speaking of which, Brad, sorry to interrupt. I just wanted to, I didn't want to bypass when things changed when I got to college. All right. [00:23:00] Remember, I go through high school. I'm fragile. I'm very careful about every movement. Right. But by the time I get to college, you go like, I am tired of this.

I'm just done with it. It was too contrary to my nature to feel so physically restricted. Right. So I thought I'm going to test this out. What do you think I did to test out the idea that I was fragile? Did you go try and do another backflip?

I would say that this was representative of who I am as a person. I signed up for judo and trampoline. And

Brad Minus: trampoline.

Alan Weisser: Oh yeah.

Brad Minus: That's worse than the back flip. At least you had No, actually, the,

Alan Weisser: actually the judo is worse. Have you, do you know judo? Have you seen Judo done?

Brad Minus: Yeah. I, I, I mean, I wrestled and I've done a little jiu-jitsu myself.

But I was more thinking about the ability to like, jump up in the trampoline and have the ability that you, you could miss again. Oh, yeah. But yeah, no, no, no. Judo is

Alan Weisser: grappling itself. The judo is more daunting because with the throws, as you know, you hurt the person by slamming them to [00:24:00] the ground, right?

I remember the first throw. As I'm going through there, I'm thinking to myself, I'm either going to be fine or I'm dead. But I had no regrets. Wow. The great irony is that I wasn't harmed. I've been in the martial arts over 50 years. And didn't find out until about six years ago, because I worked with a chiropractor, who for the first time since the accident, or a little bit after that actually x rayed my neck.

And he told me that he could see the breaks. He said, but he saw something he had never seen before, which he described as a natural fusion. Now, whether it was being on my back in a brace, I have no idea, but I had healed in a way that wouldn't have been expected, which is why my neck was okay and as always has been.

Yeah. Well, cause so. Okay. So the, so I overcame the physical restrictions. I go, fine. That's when I got into [00:25:00] judo seriously. I didn't really get back into the martial arts for several years after that, but I spent that first year doing that. I did the backflip. I managed to get it done.

Brad Minus: Yes. That's outstanding.

Yeah. And that had to be, that had to be terrifying when you decided to define, to, to go after the backflip.

Alan Weisser: No, actually, if I, if I can remember, and I'm not sure I can, I was more excited than scared. Really? Well, I'd never completed the, the jump, the flip. Yeah. I'm the kind of guy that I need to finish what I start.

Brad Minus: I, and I get that because you over, you know, you missed the first time and it caused you two years of and a, and a mindset change. But I still had to think that, okay, the last time I did this. I was in bed for a year and now I'm going to try it again. Now I get that. Now I get the fact that you wanted to do it, but I just saying [00:26:00] that first time that you're going to say that you're going to go off that board again, that I would just think that you're just be like, okay, I'm going to do this because it's in my nature to do it, but I would be spooked, but you're saying you were excited.

So I'm, I'm, that's, that's awesome. That's amazing. That's a, that, that's a complete, you know, shift.

Alan Weisser: Well, that's, like I said, sort of who I actually was before the accident and kind of got back to, at least that was the beginning of reassembling myself. That's

Brad Minus: absolutely amazing. So here you are, you're, you're in martial arts, you're you're, were you in, you're in law school at the time or this is after law school?

Alan Weisser: After law this, the, that was in college, then came law school. Yeah, so then, then law school, I'm in New York City, I'm living in New York in Grange Village. I moved from the suburbs into the city once I went to law school.

Brad Minus: Yeah, there's a, there's a, there's a pizza place that, that is that's in Greenwich Village and in and Midtown called John's Pizza, and I've been [00:27:00] there forever.

And I'll never, that's like, I can't go to New York and not get a pie from John's Pizza. It just doesn't happen. It's just perfect. That's,

Alan Weisser: that's the place. I know John's. Do you? Okay, cool. Hey, I'm a New Yorker. I lived in New York until

Brad Minus: 20 years

Alan Weisser: ago.

Brad Minus: But yeah, no, I can't go to New York without hitting John's either.

Either the Greenwich Village area or the, or the one on 44th between 7th and 8th. Yeah, yeah, it's just not gonna happen. But yeah, talk about pizza. But but yeah, that's, I mean, but just the idea of that mindset shift right there. That is like people don't come back from like, there's numerous, I'd say more than not.

And you would probably know better than I would that people don't come back from that. You know, they're always going to keep a piece of that for the rest of their lives. And most of the time it's negative, not positive. You were able to turn it into a positive and went over and above what were your, what you're even doing before.

Alan Weisser: Like I said, even though it may be somewhat unique to me, I don't think it's unique to humans at all. [00:28:00] If you understand that you have this innate potential and power to deal with anything. We are not designed to be undone by some challenge that life presents us with. We've been given infinite potential, but if we don't know how to tap into it, we don't.

I just intuitively was oriented towards that. I just wasn't and never was and never will be interested in you cannot or know. Where that's impossible. It kind of defines me because for me to take on challenges feels exciting, not daunting. I might be a little bit anxious, but I'm more interested than anxious.

Now

Brad Minus: you're talking to the choir because that's, that's where I is. That's my biggest message to people. Is that to take the next step to go up to the next level in your life is to take on some sort of challenge that's much bigger and much, it taps into your imagination and most likely it's [00:29:00] something that you would never have thought you can ever possibly go for if you put it on your list and you just keep fighting to get there.

You're going to make it and the things that you accomplish on the way are infinitesimal. And we'll, we'll stay with you a lot longer than some of the negative things that happened with you in your life. So for instance, and my audience is going to get really ticked off at me for, for telling this story again.

But like one of my, one of my friends, when I first started coaching, you know, she was five, one and 250 pounds. And she had tried dieting. She had done a five K and blah, blah, blah. But you know, and, and she'd taken some, you know, kind of yo yoed back and forth. And there was a, there was a a tragedy in her, in, in her family that caused a little bit of it.

So But when she finally decided the same thing that you did, when you said, okay, enough of that was enough. But she was trying to find a way through it. She just happened to be watching television and she caught on to [00:30:00] the Ironman World Championships. And she's decided at that point, she goes, wow, that looks really interesting.

She did her research and then found out that there was Ironmans all over, Ironman triathlons all over the country. And she was living in Florida. And she, she says, you know what, I'm going to do Ironman Florida. 18 months later. She's on the beach in a size small wetsuit weighing 120 pounds. Wow. So the goal, the challenge, was to get to the starting line healthy and fit enough to complete, to, to complete the, the challenge.

The stuff that she learned on the way, she learned about diet versus fueling. She learned how to make sure that she had good recovery. What did she need? All the stuff that she would have learned if she, if she had gone through the. I would say the normal way of going to the gym, then dieting, and blah, blah, blah.

She just did it in a different way, and it just was part of it. It wasn't the goal. It [00:31:00] was just something she had to learn in order to get to the goal. Now you're preaching. Cause that's what I, that's what I, that's what I get to all my, all, all my other people on my on my roster, you know, a lot of them are come to me with a bucket list that they never thought about and a lot of them, I'm like, no, that's not good enough.

You're going to do this instead and you're going to hit that first bucket on the way. So, and it sounds like you're doing, this is exactly what you ended up doing, but you had it in an eight.

Alan Weisser: Yeah. A funny footnote to this. You'll appreciate this. So when I eventually wanted to seriously get into the martial arts, I looked at about 20 different schools.

The school that I chose to train in, the requirement was that you train a minimum of 25 hours a week. The workouts were four and a half hours long. Wow. Okay. And you had to train in between. Well, you couldn't be in the school. Full contact, no protective gear from day one. It took me two years at training at that level to make it through a workout [00:32:00] without collapsing.

But here's the, here's the point. When I went around to these different schools, when I found this school, it was in a rickety old building in Queens, a place you probably think it's probably deserted, right? Up with four stair, staircases. And then there's this little sign next to a door that says serious training, no contracts.

That was it. Not even the name of the school, right? I walked in and I watched them train and I go like, That looks impossible. That's for me. I figured if I was going to do this, go for it. That's exactly right.

Brad Minus: That's exactly right.

Alan Weisser: And my sensei told me several years later, because I was complaining about it, I didn't think I was nearly as good at what I was doing as a lot of the other students.

He said maybe, but he said what you've got makes you more dangerous than any of my students. And I go, what are you talking [00:33:00] about? He goes, you have fighting spirit, right? You're the kind of guy that would have to be killed to be stopped. He said, not everybody has that, but you do. And that turns out to be very true.

It's probably part of the story of how I recovered from my broken neck. And then a lot of things that happened after that,

Brad Minus: you always find a way, some sort of strategy to get you to get you to the end.

Alan Weisser: Well, I did, I did tell myself when I was really young that what I put on my headstone in the, in the cemetery, this is one I'm not going to take lying down.

Brad Minus: I love that. And you, you. You better keep that. I like that. That is amazing. Yeah, I love that. Love that. That I'm, I might have to steal it. But that's fantastic. Yeah. So, all right. So what kind of, you're, you're a trial lawyer. I was a trial lawyer. Started working.

Alan Weisser: Well, I always wanted to be a trial lawyer.

I like the idea of being, I like being on stage. I like [00:34:00] arguing and debating. Always felt sympathetic towards the underdog. Yeah. It was kind of the family, my family culture in many ways that I was always, I felt actually coming out of my childhood somewhat discriminated against and sort of second man down in a lot of ways.

So I always related to people that needed to be lifted up even in my singing group, I brought people into that who weren't doing very well in their lives, but benefited from being in the group together and getting that kind of notoriety, which we got in high school. So, I think that was another important lesson learned from this about what I really wanted to do with my life, not to mention my father was the, from my point of view, the perfect teacher, fifth grade, right?

I would go to his classes sometimes and see the way his students respected him and just how seriously he took his job and how they benefited. They'd come back years later to thank him, right? So, that was kind of part of my lesson about what you want to do with people and do for people. Along with other [00:35:00] lessons I learned about humility.

I, I may or may not have been the same person I am now if I hadn't had that accident. But it certainly helped to shape me in ways that have made me who I am.

Brad Minus: Interesting. So as a litigator, so did you So start, I

Alan Weisser: started with Legal Aid Society. Okay. 'cause that was the quickest way to get into the courtroom.

If you wanted to be in the courtroom as a lawyer, usually have to pay due dues for a few years. But that would get me in the courtroom immediately. And so I started out legal Aid landlord and tenant court. That was the beginning of another lesson in life that's relevant to all of this. Picture the scenario.

I've got my first case. It's a typical slumlord, you know, immigrant family. Terrible situation. I do my research. I find brand new law that completely exonerates my client. I write a lovely 10 page brief the way I was trained, right? Picture the scene. I walk into the courtroom. There's [00:36:00] maybe 40, 50 people in the room.

I'm one of the first cases to be called. I asked to approach the bench. I walk up and I offer my brief to the judge and he goes, what's this? He goes, that's a brief in support of my motion to dismiss your honor. He goes, I don't read briefs. Tears it up Throws it up in the air and rules against my client on the spot.

Totally illegal, right? It took us two years to appeal the case. We eventually won, but it was too late by then.

Brad Minus: Oh my god

Alan Weisser: Yeah, that was my introduction to being a trial lawyer And my introduction, because I'm kind of naive and idealistic coming out of the suburbs. My introduction into how the real world can operate.

Brad Minus: So Was that judge's last name Engren or Marchand? No. Okay, just wanted to make sure.

Alan Weisser: No, this was a lower level judge in court that thought he the power to do the things [00:37:00] he did. I won't get into the story of what happened after that, but let's just say that eventually had to take responsibility.

Brad Minus: I get it that, you know, those two judges that I mentioned probably could have been around at that time and probably was doing it.

But anyway, we'll let that go. Little side joke. But, um, so, okay, so you're, you're in litigation. Now you're doing legal aid.

Alan Weisser: Yeah, I moved on eventually to working in a private practice not necessarily doing a lot of trial work. And then eventually moving on to a law firm that did a lot of prepaid legal services.

So, I loved being a lawyer. I enjoyed it. But it was already the feeling like there's something about this not quite enough. So, you know, I was at it and I was well enough. And then it, that kind of went on until I was close to 30. And then my father died and that was a turning point. Because I was already beginning to go like, what are you doing?

You've, you've followed the course. You've done what you're supposed to do. [00:38:00] But is that really you? And that's when I did probably the most important thing I've ever done in my life, and that was I just go screw it. I sublet my apartment. I had 800. I had a friend who had just gone to Amsterdam to live. And I just bought a ticket to go to Amsterdam with no plans, got my backpack, and spent months after that traveling from Amsterdam, eventually living in Marrakesh, eventually being unofficially adopted by a Bedouin and having incredible experiences.

But here's the part that really matters. I'm out in the world, there's no cell phones, there's no computers, there's none of that. I'm out there without the props for the first time in my life. People do not know who I am, I do not tell anybody much about me. So, whatever happens, it's me. There's no wondering that it's based on anything other than who I am.

And it turns out I'm actually the person I always wanted to be. How would you describe that? [00:39:00] Adventurous, and apparently a natural leader.

Brad Minus: And yeah, so at the beginning of this,

Alan Weisser: and a devoutly spiritual person in a certain way because my entry into being involved with Bedouin was I was sitting Marrakesh.

Have you ever been there? No. Well you probably, once upon a time that was a destination. Yeah, so that I was there then when people were traveling and people were out there and there were lots lots of expats in town So we're in the local what they call the milkshake Which is very funny because it didn't look any different than any of the other adobe buildings inside didn't look any different But a lot of people would go there especially expats So I'm sitting there with my friends one night and the door opens in this entourage about ten people walks in Arab people with Arab clothing and this one guy on the front That everybody's looking like, Oh my God.

Right. I don't know what's going on. [00:40:00] So he's looking around the room and he looks at me and we lock eyes and he walks right over to me and he goes, your eyes and mine are the same. We should talk. Yeah. He became a mentor and one of my best friends. He was the shaman in the tribe. Really?

Brad Minus: Oh, okay. Alright, now things are starting to move.

Now I can see, now you're starting to move on. Okay,

Alan Weisser: throughout my life, Brad, people like this have presented. My chemistry teacher, my girlfriend, this guy. Whenever I seem to need a person in my life to help me continue to evolve, and grow, and connect, and get more acquainted with me, they're there. And I think they can be there for everybody if you open yourself to it.

Brad Minus: And that's, that's an interesting point. I just got off the phone with, a friend of mine who was , a lot younger than me. And she ended up having some issues because she felt like, a lot of her friends had, [00:41:00] she's not talking to them anymore.

And that's exactly what I told her. I was like, listen, people are going to come and go from your life. They're going to come, they're going to be there for a certain reason. It's either for you to help them evolve or them to help you evolve or both and then it's not like they're just going to sit there and say, Oh, I got enough of you and they're going to leave.

It's just, they're just, it's going to fade. And that's it now, whenever you get back on the phone or you talk to them again, it's going to be like you never, they never left. But just because of you've gotten to that point where you've gotten what you've needed from both of you It's just gonna it's naturally going to go away the same way that person came into your life the same way So that's a and that's totally it's and it literally I just had this conversation So it was very interesting that you brought that up but I I believe it and I just think we sometimes we just need to see around us and Not have this negative feeling toward people, you know, somebody comes up and says hello to you Talk to them because that person might, might just be there for a reason.[00:42:00]

So yeah, I, and I, I totally get that. I've, I've had some of those people come into my life as well.

Alan Weisser: Yeah. That was also, by the way, the transition from being a lawyer to becoming a psychologist, that was the beginning of it, because that's when I began to realize why I wasn't completely comfortable being a lawyer, that lawyers have, there's a lot of restrictions to what lawyers can and cannot do with people, but they're basically hired guns.

And I wasn't, you know, my first critique from my first supervisor in legal aid. After about a year of being very successful, actually, he said, The only problem is you spend too much time with your clients. I go, like, what are you talking about? He said, you spend at least a half an hour extra with clients in time than most people do.

I go, well, you know, they're anxious, and they're ignorant, and I go, if I calm them down and educate them about the case, they'll be a better partner in the work. And his answer to that was, that's not what we do these days. You're the gunslinger, you take the job on, you just tell them what [00:43:00] to do. No, I'm not saying lawyers can't do more of what I want to do, but if it's a job about helping to empower people and enlighten people and share what I've learned and what I know there were limits in how much of that I could do in that job.

I get that. And that aspect of who I am really came forward once I left everything behind.

Brad Minus: I, and that's what, when you said that you had meant a shaman that was going to mentor you, that literally felt like foreshadowing into, okay, now this is the stepping stone to where you decided to go get your go get your PhD.

Alan Weisser: That took a while. My younger brother became a psychologist that was part of it. I had a chance to kind of sample what that looks like. My older brother was a lawyer, so I get to choose. I'd already become the lawyer, like my older brother. And so eventually I decided to go back to graduate school.

And that was very interesting [00:44:00] because I had to figure out how to go to graduate school full time and work as an attorney full time.

Brad Minus: I I have an idea. I had to work full time during the, during graduate school. I had the same thing and it was, you know, you had to be in, I was in class. Eight hours a week and and then still had to study, you know, another eight hours, nine hours a week and then still had, you know, 45 hours of, you know, I was a, I was in the military at the time and made it worse.

But but yeah, so I get that, that, that's, that, that's tough. That is super tough.

Alan Weisser: Well, once again, though, this is interesting. And I appreciate you asking about my orientation. I took that as a like, all right, it looks impossible. That's great. That's my thing. Right. What do you think? What do you think I did?

I got it. I got it done. But how do you think I got it done? Because that all by itself is an interesting story.

Brad Minus: Really? Okay. Well, why don't you just go ahead and tell me? Because all I can think of is that you already [00:45:00] had, you said that you had a system that you already had in place that got you through law school.

So I'm figuring that you brought your system back and that you ended up, I would say that you probably ended up losing some sleep.

Alan Weisser: I didn't. I didn't. And I also didn't diminish any of my training in martial arts. No, what I did was I got into something I hadn't gotten into extensively, which was time management.

So my job as an attorney was costing me 60, 70, 80 hours a week. At that point, the only good news was it wasn't fee for, it wasn't fee for service. It was a retainers. So I didn't have to worry about billable hours. Right. But I looked at it and I go, I can't put 60 or 80 hours in. I'm going to go to school 40 hours.

That's it. And then graduate school, right? I'm going at night, but I'm going full time. So, I analyzed all of the time I was spending doing everything. And I mean everything. And then I go, like, alright, is there any way to save [00:46:00] time? A simple example. To read a chapter of 20 pages would normally take me an hour.

To read with comprehension and retention. And I looked and I go, I don't have an hour. I need to get this done in a half an hour. So in order to do that, I started studying mnemonics, speed reading, you name it. Was able to increase my reading time to a half an hour, or decrease it. And develop new skills. I ended up redesigning my entire practice as an attorney.

One quick example. I figured out how much time it was taking me every week on the phone. And in those days people actually used the phone. Yeah, I get it. And it was like two and a half days of my time. And often disruptive and unnecessary. So I changed it. I told everybody I was working with on any side.

You're gonna hear from me every week during this time frame. Whether you need to talk to me or not or I need to talk to you or not. It took me months to get it. in [00:47:00] practice. But once I did that, two and a half days turned into two hours. Nice. Not only that, but I was more on top of things. People felt more connected.

Blah, blah, blah. The end of the year, I was down at 40 hours a week with greater levels of customer satisfaction and productivity. And then my boss calls me into the office and he goes, What the hell are you doing? People say, You're never here in the evenings. You're not here on the weekends. I go like, Have you looked at my numbers?

It goes, Yeah, I don't get it. I described my system and then he made me manager attorney, which by the way, saved me more time,

Brad Minus: right? Because now you're not, you're not accountable to two clients. You're accountable to your,

Alan Weisser: to the attorneys. Yeah. And I integrated my training into my, into my study and my daily work.

Bottom line is that I came out of it advanced in my training and more importantly, the depth of my study skills and my commitment to good use of time and memory. is the reason why I'm actually sitting here today with this model that [00:48:00] we developed. Because my understanding of psychology and the depth of my knowledge about it was honed on this level of study that's beyond what most people would have done.

I studied every course like I was going to teach it. So my retention, I can still remember chapters out of a book.

Brad Minus: You know, that's, it's interesting you said that because I remember being in school and we having certain lessons and the way that we were taught and we were, that we were Some, some of the courses were like, okay, you're gonna take this, this chapter and now you're going to teach it to the class.

So when we read the chapter, you're right. It was much different knowing that, okay, I've got to take this now and I've got to be the one to brief the whole class on it. There's a much different level. Of getting into that, knowing that you've got to present it rather than just you feeling like you've got to learn it, which is a negative at that point, because if you, like you said, if we were, if everybody was able to look at that and go, okay, well, listen, [00:49:00] I'm going to read this chapter as if I have to teach it, it would be people would all would, would gather that greater knowledge and that greater comprehension.

So that's, Yeah, I I commend you on that. So real quick when you got done with your with the with the clinical when you got done with yours with the Ph. D. Where did you did you actually become a clinician clinical psychologist.

Alan Weisser: Yeah, but just do you give you a quick jump through it?

So I'm going to school in New York, the New School University. And in order to complete the PhD, you have to do a year inpatient internship, which, by the way, I wish every therapist did because there's no better training than working with people that are psychotic inpatient. So I took, I got an internship at Bronx Psychiatric Center.

Once again, I almost didn't get accepted. It was one of the best internships in the country. I won't get into it. You and I could spend hours talking about my side [00:50:00] stories. But let's put it this way. I found a way to get in even though it didn't look like I was going to. But in order to complete my dissertation it was taking a long time.

I completed my coursework. But the dissertation, that's a long story as to why, but it was taking me. So I decided to stay. at the hospital after I finished my internship one year. And that was the beginning of why I do what I do today. I spent 10 years working in a hospital with a chronically mentally ill.

And what I learned from that, essentially, not only did I learn how to work with every discipline, because it was always multidisciplinary, But I also learned that you don't treat the disease, you treat the person.

Interesting. Yes. I also learned, what therapists usually learn the hard way, that the quality of any therapy is based on the quality of the relationship.

Brad Minus: Interesting that you said that. I, with, with somebody that is so, that is, [00:51:00] that is busy as you are, I don't imagine you get to watch too much television.

But there's a new show that started this season called Brilliant Minds. Yeah, I watch it all the time. I actually Oh, you do? Okay, great. That's why I was, I was like, wow, he said Bronx, he said Bronx Psychiatric. I'm like, that's exactly where it's set.

Alan Weisser: Yeah, well, and Oliver Sacks, that's who this story is about.

I don't know if you know that. Oliver Sacks is a real person, that guy is a real, based on a real person. Oh, I didn't know that. Read up on Oliver Sacks. Okay. There was a movie with Robert De Niro I think called Awakening years ago. Same guy. Same guy.

Brad Minus: Okay. Alright, you know what, I didn't make the, I did not make the connection.

Alan Weisser: I didn't meet Sacks. He was there right before I came, but certainly knew of him and met with some of his patients and a lot of people who work with him. That's based on him. So yeah, I watched that show. It's very good show. Okay.

Brad Minus: Well, that's, that's the reason you mentioned, as soon as you mentioned Bronx psychiatric, I just came to me.

[00:52:00] I'm like Zachary Quinto.

Alan Weisser: The cool thing about Bronx psychiatric is, is a teaching hospital. Yes. So the best technology is the best people in the business. We were constantly having people come in and teach. And learn. So including a program called Psychiatric Rehabilitation, which most people don't know about, which has a lot to do with what I do, but it's, it's based on empowerment, right?

And it's based on a very simple concept. The first step towards empowerment is acknowledging negative realities. And how often in life do people make more problems for themselves because they can't handle the truth. So I learned, I had incredible supervision, I had nine supervisors, the head of my department was my own supervisor.

Although the funny part, you'll, you'll like this piece, several years into this, of course I figured out how to do it the way they taught me, and then I added my own particular twist, which is what always happens. And I came to supervision one day and he goes, you know, I'm watching what [00:53:00] you're doing, I'm watching how well it works with your patients, I don't know what the hell you're doing.

He said, but whatever you're doing, don't stop.

Brad Minus: That's exactly how it works out. I've, I've been, I've been there and I want to, in my, in my corporate job, I've, I've, I've been in that situation to learn the way it is. it all of a sudden it works. And then everybody's like, yeah, yeah, no, no, no, no, no. Don't change it, even though it's not how we taught you, it's fine.

And it's working. So, and then how did you do it and brief the CEO on it? So I, that's, that's kind of where it was for me, at least. So interesting. So you, you're, so you started to, we're starting to get into your. that you have developed for your own practice. And you said the first part is empowerment and that's, and you said that's acknowledging negative realities, right?

So how, what does that look like? So when, so someone comes in and it maybe it's a patient of yours and now you say, okay, first step knowledge, negative realities. What does that look like? [00:54:00]

Alan Weisser: Depends on what we're dealing with. My intake packet for my patients is 65 pages long.

Brad Minus: Oh my God.

Alan Weisser: Yeah. And it's mostly inventories, but I've learned over the 25 years of working with chronic pain patients that there's any number of collateral damages.

For example, sleep disruption, physical deactivation, deconditioning, more importantly, things like loss of identity, continuity. Do you know that most people don't realize that we have a sense of continuity in our life? The things, certain things, most things remain relatively the same from one day to the next.

But with chronic pain, that's gone. The continuity gets broken, the predictability gets broken. Those are major existential impacts. So, there's up to 200 of these kinds of impacts on people in the way their lives are affected by having a physical problem that the medical profession doesn't look at. The medical profession maybe looks at 10 percent of that.

You [00:55:00] may have difficulties, you know this, if you've done the work. There may be limits physically to how much you can help a person, although I do make sure that they get the ultimate outcome with their treatment. There's no end to how much you can help a person be empowered. I mean, life's full of examples.

Stephen Hawking, how do you do that? Right. How do you do that? How do you be Christopher Reeve? How do you do these things that we find inspiring? Well, the answer is very simple. We all have the potential to be able to do that. Now as to why that's possible with some people other than people in general, what I did learn work, and it doesn't matter who they are or what walk of life they have or what level of success, what really gets in people's ways ultimately when they're confronted with something like chronic pain, or COVID, or some other major something, they find out they don't love themselves.

Not truly because if you don't you don't have full access to your power and a lot of the work I [00:56:00] do is clearing out those blockages and cleaning that up and reconnecting them to their birthright

Brad Minus: There's a lot of people that don't have chronic pain or suffering that don't love themselves and don't realize why they're not accessing their power Yeah, matter of fact, I would say over 50 percent of the people don't realize that

Alan Weisser: Well based on the state of the world may be a bigger number

Brad Minus: Yeah, but I mean just the people that I know that that are around by the way, this,

Alan Weisser: this approach was evolved working with chronically mentally ill and chronically pain patients.

But it actually, you don't have to have those. It's any chronic suffering, right? We are not designed to suffer on a chronic level. We're designed actually to learn from our suffering and make our way through it and come at the other end in a higher state of functioning.

Brad Minus: Exactly. And it's interesting [00:57:00] because my clients and what I do and in my athletic pursuits, suffering is part of it.

It's, we know it's happening and matter of fact, it's weird when we don't suffer, but again, it's not chronic. It's only for that short period of time until you finish the race, then it's over. But every single time that I've gone through it, I've learned something on the other, on the other side.

Alan Weisser: Yep. Yep.

So you know, it's part of life and I know people say that and they talk about it. Living in it is not so easy, but I, like I, like you've heard already from things I've been through and a lot of things I haven't mentioned. I've almost died five times in the water. I have some kind of karma with, with the ocean.

But each time that fighting spirit came back to save me, and I don't think I'm unique and having that. I just think I I may be one of those people is more connected to it than the average person. But I think that's that's the life force.

Brad Minus: I get that. [00:58:00] And I'll tell you, I'll tell you, I have people that I've trained that were competitive swimmers in the pool.

But the minute you got them out into the open water It was over. It's like they lost everything. They didn't they didn't realize that they could actually swim. I've had to save somebody who was a competitive like Olympic caliber swimmer from the from from the from the sea. And that's and that was, you know, so interesting to me that, you know, here it is, is this person could like fly by me at any moment in time and you get him out into the sea and something just cripples him inside.

So But yeah, that's that, that's something that I wouldn't wish on anybody. But definitely almost died almost five times and having to do with the water. I mean, obviously the first time was, was your accident.

Alan Weisser: No, actually the first time was when I was eight years old and I was visiting with an ant swimming in a nearby lake.

And I like to go underwater and swim underwater, hold my breath, managed to get [00:59:00] myself tangled up in a bunch of vegetation at the bottom. I was out in the lake all by myself, of course. Somehow I managed to get free of it, but that was close. So even before the broken neck, but that was just a different kind of encounter.

Brad Minus: But still, excuse me.

Alan Weisser: To know that I could die, I actually, if I think about it, I actually learned that at eight.

Brad Minus: But it still was that, that fighting spirit you said. Yeah. That's what got you out of it.

Alan Weisser: That's right. I was not about to die. I found my way out of it, and that's so far what's happened with anything I've run across.

Brad Minus: So, in your practice, are you, like, Is that something that you're pulling out of people?

Alan Weisser: I wouldn't say I'm pulling out of people. I'm helping people to see they have that. I'm, like I said, sort of, the, the work that we do started [01:00:00] out with an idea about chronic pain and that chronic pain is the result of multiple damages, not just the injury.

And then sort of assessing that and then going like, what do you do? I remember sitting with those patients in the beginning going like, What do I think I can do to help somebody with that kind of physical suffering? That led to me beginning to develop what's now known as the existential immune system.

And it turns out we don't just have a physical immune system, we have an emotional, psychological, and existential immune equipment. That we have this amazing set of equipment, evolved for millions of years, which we seem to be unaware of. That there's this equipment And there's a toolkit, and we began to understand what those tools are, how to use them.

I'm not just theoretical, we operationalized it. We go like, okay, if that's the theory, what does that look like? For example, if all human experience is [01:01:00] translated into thoughts and feelings, which it is, what does that tell you about thoughts and feelings? It says they're really important. And then the question is, are they operating the way they were designed?

Well, it turns out that if your thinking process is colored by self judgment, Assumptions, rationalizations, generalizations. There's all these forms of thinking that are counter revolutionary. They don't help. They don't represent the truth. You look at conspiracy theories in the world right now, and belief systems, look at how much damage it's doing.

Because they don't represent the truth. Right? And then, emotions? Well, it turns out that emotions are actually tools. They have a functional purpose, they're not just an experience. And the two most important emotions, can you guess which ones they are?

Anger and frustration. Frustration is a form of anger. Anger is one, anxiety is the other.[01:02:00]

In shorthand, anxiety is a fire alarm. You'll never experience that emotion unless your needs are being threatened. Ever. And then once you've experienced the threats to your needs, anger gives you focus and energy to deal with the threat. The only reason, they're not pathological. People talk about anxiety and anger like they should get rid of them, they're pathological.

They're not. If they're not used properly, they become pathological. A gun's not bad, but if you put it in the hands of a baby with no safety, what happens? So we have these tools, we don't know how to use, they're causing us harm. You know, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, that's, that's not the emotion, that's a misuse of it.

And why did I get to that? Because my chronic pain patients had so much more anxiety and anger than even my other patients from previous experience. I'm going, it can't all be one sided, because nothing in human experience is one sided, it's all two edged sword, right? I go, there's the suffering [01:03:00] caused by those, but functionality.

That was the beginning of the revelation, so that evolved into a technique called the Survival Triad, which will get you working down anything you're anxious about in about one, one hundredth of the time. It's much more efficient, much more effective, it's revelatory. I went through psychoanalysis for 15 years.

This approach can get the job done in five. Really? Yeah, and that's not a brag. I've helped over 3, 000 patients that we've used this approach with. And I, I'm, I'm classically trained. I went through psychoanalysis. No, it's like anything else. Like what you said earlier about finding a more effective, efficient way to do something.

Why not? I even changed martial arts about six years ago after 45 years in Japanese systems. Because I found what I thought was a superior system, which is Wing Chun, if you're familiar with that.

Brad Minus: Yes.

Alan Weisser: Yeah,

Brad Minus: the Chinese, Chinese Kung Fu. [01:04:00] Yeah. And you, oh, you felt that Wing Chun was superior to Judo? Wing Chun is superior.

Or just the Japanese sense, the Japanese martial arts theory, philosophy,

Alan Weisser: let's put it this way. I wouldn't so much say superior is more efficient than effective. It doesn't require big movements. Unlike most martial arts, jiu jitsu is a better example, actually, or even Aikido. But with Wing Chun, you, once you connect with your opponent and you do a lot of sensitivity training, you know, train with blindfolds, you know, you've seen sticky hands, you know, that technique.

So I'm going like, that's, that's doesn't require big movements, which probably a good idea because I've got some back problems. But in a real fight, you know how it goes in real fights, people are grabbing each other, they're trying to take each other to the ground. So a lot of those techniques that you use in karate don't work that well unless you've got distance.

This technique requires you have no distance. You want to connect. So, that's been lots of fun. Not to mention how hard it was to overcome certain muscle [01:05:00] memory. But, always looking for some other way that seems to get it done more effectively.

Brad Minus: I 100 percent get that. So when I So when I hurt my back I was in the middle of training.

I was middle of training for my for my second marathon. And my second marathon was 10 years after my first because I took after the after the first one, I said I would never do it again. But anyway, so I was in the middle of training for my second one and and I brutalized my my My L5, my L5 S1 to the point where my neurologist and my my orthopedist both said that I would never run more than like two miles as a warmup, very slow for the rest of my life.

Alan Weisser: Wow.

Brad Minus: And by the way, that was 37 marathons ago, not to mention five Ironmans and a bunch of other stuff. But it, so it's the same thing, right? But it was finding the efficiency and I developed a way of running. That took all the pressure off my back. So same [01:06:00] way, but it was fine. And then when, so now when I, when I teach it and when I instruct it and I put on clinics and stuff, I put, I put clinics on for, for eight years, back to back to back to back.

It wasn't about making them faster, making, getting them endurance, which was part of it. It was about form. And function and efficiency. So I'm not teaching you to be fast. I'm not teaching you to be, you know, I'm not teaching you endurance that will come, but I will teach you is how to be efficient on your feet.

And of course, as a triathlete, that was major because once you come off the bike, you need to be as efficient as possible because your legs are dead already, you know, your whole body has been been through the ringer and yet you still got 26. 2 miles left to go. So you need to be as efficient as possible.

Yeah. But yeah, so I, I told, I totally get that, but I'm, I'm truly excited. About about some of the little bit things that you talked about the, you know, the triad, the ability to recognize the negative realities all that stuff. [01:07:00] That is really, really, really exciting. I think you can help a lot of people and and I'm even more impressed with.

You said that ability to help anxiety patients in a fifth of the time. And that's because I, I deal with that as in my, I, I also coach high school cross country and track and field and just the world around us. You know, you know, we've got people, I've got kids that refuse to get their driver's license, like you and I.

We were like, as close to my 16th birthday as possible. I want to be at the DMV and I want my key. And then I'm that night, I'm going to ask my parents for the keys. They're not going to give them to me, but I'm going to ask them for it. But yeah, you know what I mean? We were like, that was like, ah, that's our first sign of freedom.

You know, I'm here in Florida. We have a community college called Hillsborough community college. There's a car lane, just like high, just like elementary school. [01:08:00] There's a car lane. So parents can pick up their kids from. College. That's sad. Because there are more people, more of these kids that don't want to drive.

Okay. Part of it is social media and the ability that they can do a lot of things from their home, just like we're doing right now. We're having this conversation. But the other part of it is, is that it's an anxiety. Now, all of a sudden, because of everything that's going on, these kids are literally afraid to get behind that, get behind the wheel of a car.

Alan Weisser: Yeah. Unfortunately, they can get worse.

Brad Minus: Yeah. And, and I've talked to some of these kids that are like, Oh, no, no, no, no, no. I'm not, no, I'm not going to drive. I've had, I've, I had to I had to coach a kid that was a sophomore in college and she was taking her military physical fitness test and needed to need help on her three mile run.

And her dad had to drop her off. Her younger sister drove before she did. And her younger sister drove, dropped her off at sessions all because she wouldn't drive. Yeah. And now [01:09:00]

Alan Weisser: this is if you want anxiety level. Yeah. If you want a way to cut through this. Here's the tricky part. It's the way people think about anxiety, even the way you're talking about it.

Anxiety is not a problem. It's a tool. If you said to a person, okay, if you're anxious, there must be needs that are being threatened and all needs are under the love of self and love of others. You go like, okay, are you afraid for your physical safety? Right. Is that the, the threat? 'cause that would be a need.

Right? Are you afraid of something else? Once you connect the person to the actual need that that's at risk, it's a lot easier to work on it than on feeling anxious. Because most people, when they feel anxious or angry, want to move away from it. And you and I know, there's a lot of things in life we don't want to deal with.

I don't want to know, right? But we also know, if you don't get into it, if you don't embrace it, it's kind of like when you're suffering over a loss, but you don't embrace the suffering, you can't grieve the loss. All right, people have this, have this bias against suffering, [01:10:00] an actual bias. I don't like it any more than anybody else does, but to discriminate against it because it's unpleasant and not understand that it's part of being alive and that it has its own value just as well as good stuff does is, is life changing when people begin to understand that and be more willing to, the stuff that I've made myself get into, because I know if I don't, it's going to get worse.

That's very difficult in our country. That's part of the problem in our society. I think it is too many of us have been anesthetized and sort of enabled to not have to take on the tough challenges. You know, where's the good old American spirit?

Brad Minus: Yes.

Alan Weisser: Yes. Yes. Where's the mentality you have and I have in the general public?

I don't see it.

Brad Minus: No. And, and I get it. Because, you know, first timers in the in the Ironman triathlon, 80 miles on the bike [01:11:00] is about the point. And we, we even say that we even say that Ironman doesn't start till 80 miles on the bike. You got 32 miles left on, on, on the bike. And you got a 26. 2 miles left on the run.

That's where the suffering starts right there. And more people quit right there than anybody ever has done because they don't know what it's like to suffer. And they weren't trained. You know, obviously, which is why I do what I do is I can help them through that suffering. But when they get through it, the world opens up to them.

And it's amazing to see what goes on in people, in people's lives after that.

Alan Weisser: I have a book to recommend to you that or may not have heard of. My, my sensei was fairly young guys in his forties. Long story as to his background, but he wrote a book called strength through stress. He's one of the exponents of you.

You're familiar with the Wim Hof method, the cold and therapy. Yeah. Yeah. Been through it. Well, he is one of the trainers in that he works with Wim Hof and has for [01:12:00] years. But strength through stress is something you're very familiar with. Will you tax yourself physically as a way of dealing with stress to get to the empowered side of it.

And whether it's Wim Hof method or using Asana or doing hard training, he's got a technology. The book is really, really well written. A guy's name is Matt Soule. So I get that. I think that's part of what you and I have learned about taking on physical challenges.

Brad Minus: Yeah. No, no, no. That's definitely it.

Matt Sule. Do you know how to spell that last name?

Alan Weisser: Yeah. Sule. S O U L E. S O U L E.

Brad Minus: nAlanank you. Thank you. Thank you. Wow. Well, hey, you know, Doc, this has been super enlightening and everything that you talked about. So just to let everybody know. So Dr. Weiser has he has a practice. It's called new options, Inc.

[01:13:00] And it's in it's in Seattle. He has his. His web address is new options, inc. com. And you go check that out and he's got, he's the, his books on there. There's, he's got some courses, a blog And then, of course, his book, New Possibilities, Unveiling the Mystery and Mastering Chronic Pain that can be found on Amazon, and there'll be a link to that in the show notes, along with his website.

And are you, are you active on any social media?

Alan Weisser: I have accounts. I don't do much with them but we do have a person now that's sort of taking on that function. We're, we're relaunching the whole program in January, including live webinars, a lot of the technology, you'll appreciate this. I think of the techniques we've developed as an existential martial art.

I even have a ranking, I even have a ranking system for the patients.

Brad Minus: That's [01:14:00] that is brilliant. You gamified therapy.

Alan Weisser: Yeah, it fits. That's

Brad Minus: outstanding. Okay. So you all have to fricking get on his site and hopefully you're going to see some changes and you know, drop a, drop a comment or something and we'll make sure that you're, you're involved, but

Alan Weisser: People should be aware by the way, Brad, that they don't have to see me as a

they can see me as an educator. There's things that are educational. A lot is an educational model, so we can work on a consulting basis. They can come to the live webinars. We're trying to put out a lot of things that people can make use of that don't cost a lot of money. So all coming. If they pay attention to the websites, they'll see everything that new that's coming.

I have my second book in the works with a working title in big letters, human, and below that a user's guide.